The physical sciences are all about observation, measurement and statistics. Our “scientific method,” in fact, requires the ability to repeat, measure and verify results; lacking that ability, a hypothesis cannot be “proven.” Despite the fact that on an individual level, human beings are far too complex to test accurately, the scientific method has also been regularly applied to social science, nonetheless.

Certainly, statistics can be generated though the simple observation of large numbers of people; how many out of 10,000 people buy blue shirts, are left handed, purchase the first apple they touch in the bin, and so on. Such statistics are used with some success by marketers to forecast and predict buying habits and purchasing patterns.

Opinion polls are another form of statistics, though their predictive use includes a greater margin of error. The same can be said for “intention to purchase” surveys, in which people are asked whether or not they might purchase a product or support a candidate in the future. These are all well and good, as far as they go, but once again relate to issues of marketing: candidates, voter initiatives and material goods of all types. To the extent that such information brings comfort to some in knowing they share their taste with others, such statistics may even contribute to a more cohesive society. However, these particular ties that bind are, in the hierarchy of values, rather inconsequential.

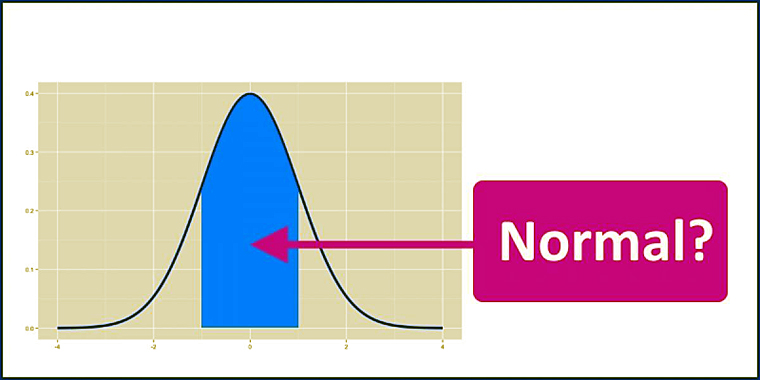

The flip side of our obsession with statistics is more harmful – namely, the notion of “normal.” As a culture, we may be superficially comforted by feelings that we share our values and habits with others, but this approach has also resulted in our penchant for labeling and disparaging others who differ as “abnormal.” Statistically, “normal” represents the mid-point on a curve, dividing aspects or character. This is informative when applied to the crowd, but entirely irrelevant when applied to the individual.

Individual human beings are highly complex, and well beyond the expression of simple statistics. The reasons we do or do not behave in particular ways are a function of myriad unknowable variables; thoughts, habits, fears, phobias, desires, upbringing and so forth. This make it impossible to calculate with certainty what is normal. Not that we don’t give it a try. Astrology, numerology, Eneagrams, psychological diagnostic scales, palm reading, and the methods of Madison Avenue are all attempts to place individuals within some statistical curve establishing norms.

What is the normal way to blow and wipe one’s nose? Unless you are in the facial tissue business, who cares? The same can be said for which leg goes into your pants first, whether you eat from the left side of your plate before the right, and so on. When it comes to the endless particulars of everyday life and human behavior, normal does not mean a thing.

Too many of us, particularly the young, spend time afraid of not being normal and plagued by fears of not fitting in, even though no normal person actually exists. In fact, we are all in our own unique ways, abnormal. It is this diversity and boundless variation that defines us; we are united in our abnormality, and this, dear reader, is the one and only thing that makes us normal.