The recent Broadway revival of the ‘60s musical “Hair,” along with my increasingly barren pate, prompts reflection on our contemporary obsession with matters hirsute. Americans spend billions of dollars each year to increase hair, and billions yet again on products to decrease it. We style it, shave it, cut it, color it, stick things in it, on it and through it. Of all our vanities, hair may well be our greatest.

Genetics and sex hormones determine where we have hair and at what length and density – what’s called a secondary sexual characteristic. The human body is covered with fine hairs emerging from countless pores that, along with hair, exude oils, pheromones and other substances onto the skin. Direct contact with body hair plays an important role in our highly sensitive perception of touch. Our lips are notable for their complete absence of hair; the palms of the hand are generally hairless too, as are the bottom of the feet. These locations are significant due to their extremely high concentration of nerve endings. Of course, there are a few other sensitive hairless spots as well, but modesty demands I leave those to your imagination.

That I am not immune to the great cultural obsession with hair is made obvious by the meaningful part it plays in my personal narrative (no pun intended). When I was but a boy, I was required to have a crew cut at my father’s insistence. A World War II vet, his own military hairstyle seemed to dictate mine. I would go to Al the Italian barber once a month or so, grab an Archie comic, and slide into his leather chair. “Don’t cut it quite so short this time,” I’d tell him, “leave it longer on the top, ok Al?” “Sure,” he’d say, wrapping a white sheet around my neck and closing some snaps. When he was done, my hair was always short. I’d say the same thing at every visit, and yet he’d always cut it short. I thought maybe he didn’t understand English. Perhaps, I surmised, Al the Italian barber only understood the word “short.” Years later, my mother confessed that she’d call him in advance and tell him to ignore me.

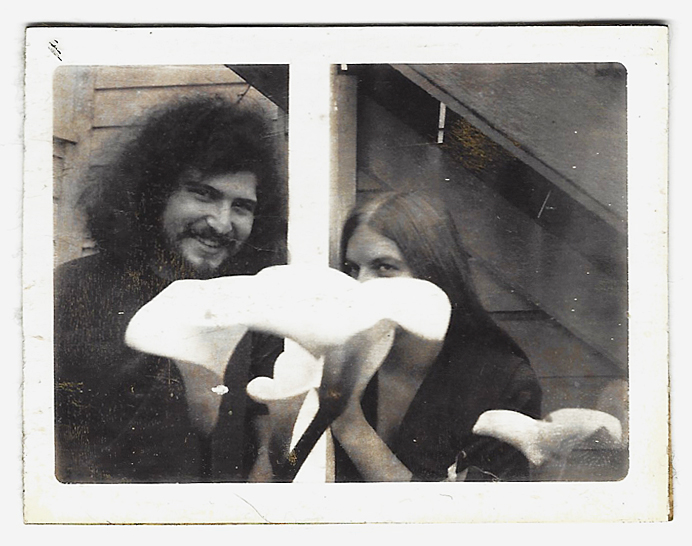

Thus it was in 1966 upon leaving home at 18 years of age, I left the era of crew cuts behind. In fact, I left it so far behind that by the time I turned 21, my hair had grown past my shoulders, Beatles style, and it remained that way for the next decade. You’d be hard pressed to guess it now, but back then my hair was thick and curly. On a humid day it would puff up into a ball-like form, what I used to call a “Hebrew Natural.” Sometimes I would pull it back into a ponytail, but most of the time, like Lennon and McCartney, I just let it be.

And then, when I became 30, my hair began to thin and disappear. Not long thereafter, I cut it shorter, and by 50, having lost most of the hair on the top of my head, I returned to the humble crew cut. Today I use a “number two” electric clipper setting and each month I take ten minutes to cut my own hair. “Leave it longer on the top,” I tell myself, but it comes out short every time.