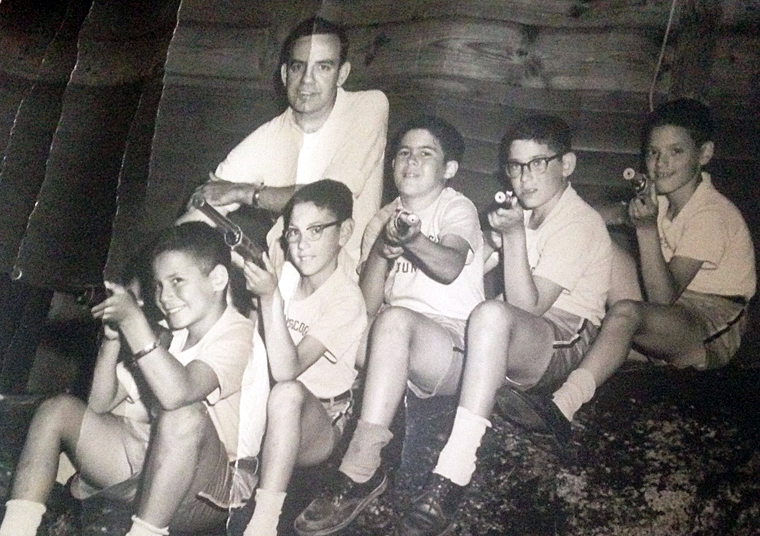

My first major exposure to the culture of the hero was at summer camp in Maine. Like many suburban New York boys, I was shipped off for eight weeks each summer, beginning at the age of eight.

Camp Androscoggin of 1956 (a mere 11 years after the end of World War II) was a military-style camp, located in the Adirondacks beside a large lake of the same name. We wore caps and uniforms of gray and lived in “bunks.” Each morning began with a bugle, followed by saluting the flag and hand inspection before breakfast in the “mess hall.” Breakfast was followed by a brief period of cleaning each bunk in preparation for inspection. Cubbies and beds were reviewed, and if unsatisfactory, everything would be thrown in a pile on the floor. In this way each day proceeded, until the bugle sounded “taps” at night.

I learned early on that failing or passing bunk inspection was entirely unpredictable. The process was arbitrary and clearly designed to provoke fear. One never knew when he would be the designated victim, would humiliate himself and the entire bunk. Tears made things worse, an almost guarantee that one again would be the victim. And identifying the weak and vulnerable, of course, was the whole point.

In short order both victim and hero would emerge. By week two, leading roles were fixed for the entire summer. For the majority who escaped either fate, there was the job as supporting cast of adoring or taunting mob. Having been identified, the chosen weakling was a daily object lesson of the misfortune that might befall us, and a ready target of anger and blame. The hero, and there was only one per bunk, was inevitably the best athlete, receiving endless praise and privilege.

The entire summer was an ongoing lesson about heroes and victims. Tests of courage and the ability to endure and inflict pain, gaining acceptance by the strong and rejecting the weak, hiding feelings of insecurity and promoting demonstrations of valor were our daily fare, enforced by college-age counselors too caught-up in a culture of competition to understand the damage they were doing. My talents were two: I hid when I could, and when I couldn’t I was funny. Neither hero nor victim, I was mostly an observer, though at times I was forced to take sides; I regret those moments of non-virtue, even now.

For millennia young boys with pliable hearts and minds have been taught cruel games, couched in language about honor, bravery and loyalty. And for these same millennia, male violence, aggression and the role of hero and victim have been tragically played out, dominating social narrative. It is an ancient Neolithic tale writ large, and you could hear it plainly in today’s nasty presidential campaign, underlying comments about weakness and strength and reactions of the press and the public.

I came away from four years of camp sufficiently capable of mixing with the mob, but my sympathies were with the victim. No doubt I too would have been a victim had I been less funny, agile and clever. I met all the qualifications: overweight, lousy athlete, too sensitive.

It took but a few childhood years to build my protective shell, and sadly, most of my adult life to remove it.