As the financial collapse continues – home prices falling and more job losses announced every day – attention has focused on stimulating the economy. The injection of trillions of dollars by the government into the banking sector and virtually every other segment of the American economy has been viewed as the way to prime our economic pump and get the economy cranking again. But all this begs the question: what type of economy do we really want?

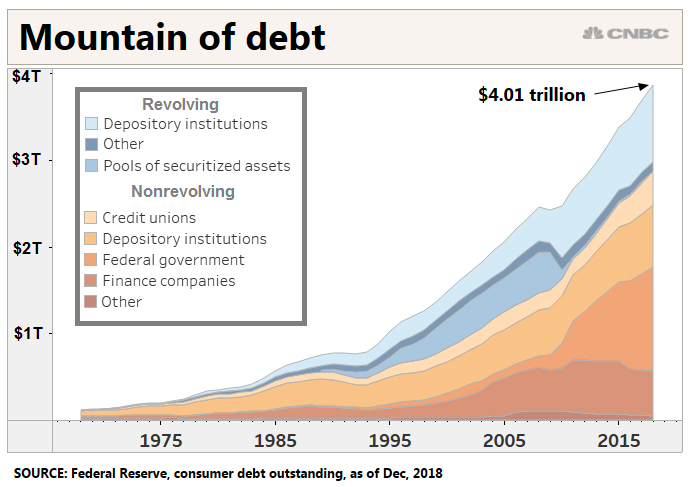

For many decades our economy has been based on growth, and all borrowing and lending is predicated upon the assumption of future growth; accordingly, businesses, government and individuals have amassed the largest debt in the history of the world. The savings rate is at an all-time low while business failures, foreclosures and personal bankruptcies are moving towards an all-time high. It’s the perfect economic storm.

The value of our currency floats against the currencies of other countries, which means that as confidence in the dollar declines, so does its value. Moreover, our dollar’s value is based upon our ability to repay our debt, which ironically is held by foreign countries who at present have invested in long-term American government securities. Thus, what props up the value of our dollar is simply the continued confidence in the value of our debt instruments, and that confidence may be flagging. If the European Union, for example, is more successful than the United States in stabilizing their economies, it may well be that the Euro becomes the safe haven for foreign investment instead of the US dollar.

Underlying all macroeconomics, however, are assumptions about the future. If consumption of goods and services does not resume, or resumes at a far lower level than it has been in the past, the forecasts about future income available to pay debt become meaningless. In a technical sense, the entire global economy will go bankrupt, unable to meet its debt obligations. None of us knows what such a world looks like or how it functions.

Perhaps this economic slowdown provides the moment to evaluate how a truly sustainable economic system functions, and to consider that the type of consumption that got us into this mess is most likely not the solution to solving it. Perhaps we need to examine the economy of enough.

When people were nomadic, enough meant what you could carry. When ancient fixed agricultural communities were developed, enough meant what you could store against an uncertain future. In today’s modern age of seemingly unlimited credit, wealth and resources, enough has lost its meaning. The feverish consumption of material resources has its analogy in our over-consumption of food, and we carry our financial debt as heavily as the extra pounds around our middles. As a nation we are suffering from a case of economic diabetes; our major financial organs are failing.

Though the media continues to hawk products and inducements to consume as if nothing has changed, we have been forced to consume less. As this continues, we may rediscover and renew the meaning of enough in our personal lives. As a world economy, however, it’s difficult to imagine what the economy of enough might mean. One thing is for certain; it wouldn’t look anything at all like what we’ve had for a very long time.