Most people I know don’t think about hell too often. I brought it up cheerfully at breakfast the other day but perhaps it was too early to talk about it; everyone just stared at me. Then again, I might have just been the only morning person at the table.

Of course, there are some people who think about hell in a serious way; those who study it for reasons of scholarship, and those who believe that there is an afterlife and hell might be their destination. I fall into the former category. For those in the latter category, staying out of hell must feel scary as hell; the list of relevant sins is all too familiar.

Dante Alighieri, the Italian poet of the Middle Ages, described the realms of Christian hell in exquisite detail in his Divine Comedy; in each of its nine circles, or levels, punishments are proportionate to the level of sin. For example, Circle Three is for those who seek pleasure only, and they are buffeted and thrown about in darkness by an unrelenting wind. Circle Five is for the wrathful and gloomy; the wrathful attack each other and tear each other’s flesh while the gloomy are sunk in thick mud from which they gurgle hopelessly. The violent inhabit Circle Seven, a stench-filled land of boiling rivers of blood and a continuous rain of fiery embers where centaurs pierce inhabitants with arrows. Finally, in Circle Nine we find Satan in his dwelling, a frozen icy realm devoid of all light or heat; this level is the resting place of traitors.

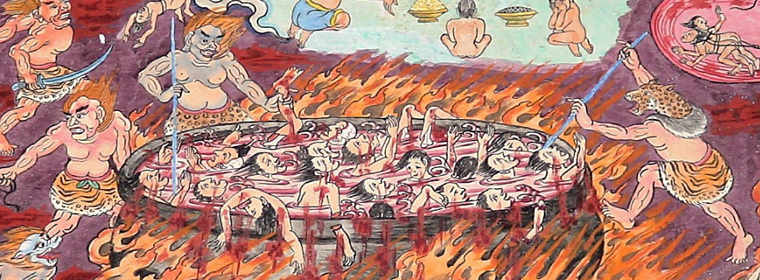

Buddhist hell is no less complicated; those who commit wrongdoing are reborn in one of many hell realms, eight hot, eight cold, and others just downright rotten. As in Dante, there is the hell of being continuously attacked by others, called Reviving; after being “killed” a voice says “Revive” and the slaughter begins all over again. Murderers are reborn in the hell called Crushed Together, where they are repeatedly crushed together to dust for eons between two mountains. In Crying Hell, alcohol abusers and those of great non-virtue inhabit a realm of burning metal houses where they cry ceaselessly from loneliness. In Very Hot Hell rods of burning iron are wrapped around each and then the tormented are tossed into huge vats of molten metal. The cold hells are the counter-point to the hot hells; like Dante’s Circle Nine, solid frozen bodies split into tiny pieces and painfully fall apart for near eternity. As if this is not enough, there are the neighboring hells called Plain of Razors, Grove of Swords, Iron Grater, and Extremely Hot River; I leave them to your vivid imagination.

One can view all these elaborations as simply metaphor, that everyday life can be hell. When it comes to people, we’ve all known the tortured, the gloomy, the cruel, the drunk, the depressed, the wounded, the vicious and so on. Though empirical evidence eludes us, an afterlife, it seems, is not required to enter hell.

While fear of future retribution can be a powerful incentive, virtue need not be exercised solely to forestall that; the virtues of kindness, generosity, love and compassion all contribute to a better here and now, and that alone is reason enough.

If you doubt that, of course, it never hurts to hedge your bets.