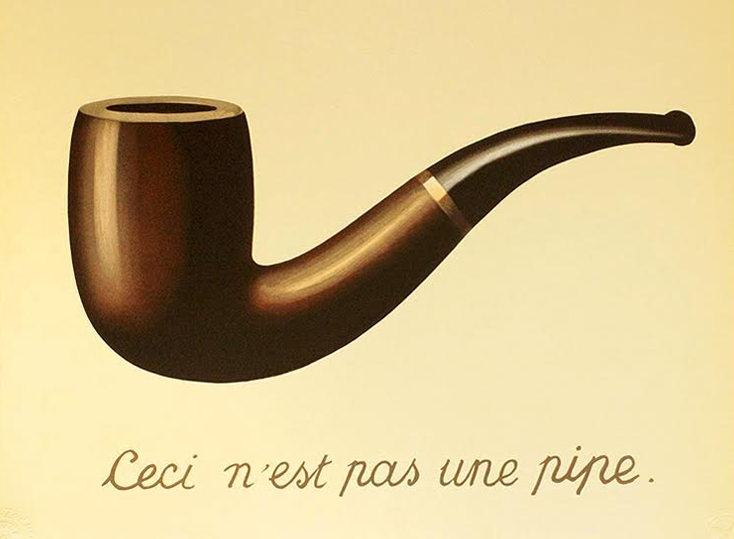

All objects are devoid of inherent meaning, which is to say for example, a chair is not a chair except in the mind of the perceiver. To a squirrel, a chair is simply something namelessly convenient upon which to settle while cracking a black walnut; it has no “chairness” of its own. The same is true for all objects; their meaning is imparted by people to each other through explanation, example, use and language.

Once objects assume meaning, they populate mind and act as ready frames of reference. Over time, we use these frames of reference to classify objects within categories, continuously adding to our array and adding new categories as they come to our awareness. One way to conceptualize this full array of objects and frames of reference is called “Mandala,” a Sanskrit term meaning circle, a circle that encloses an entire universe of meaning.

Mandala symbolizes the unity and totality of our experience; though comprised of unlimited objects of myriad description, the meaning imparted to the individual objects of Mandala is ultimately personal and unique to each of us. We can communicate a portion of that meaning to others using gestures, words and images, but our Mandala of meaning largely remains an internally interdependent web of complex relationships tightly tied to our emotions.

Though devoid of inherent meaning, in the context of our Mandala a favorite chair assumes powerful meaning. Thus, we may come to “love” a favorite chair, and the thought of losing it causes emotional distress. To others, it may look like a ragged, worn-out relic, feel uncomfortable and be ready for the dump, or conversely, may be an object of their good memories, warm feelings and desires. When it comes to one’s Mandala of meaning, all things are possible.

I recently confronted my Mandala of meaning while working with items from my late mother’s apartment. Many of these objects are things I grew up with; lamps, chairs, tables, framed photos and paintings, bowls, drinking glasses, and so forth. I held some of them at my childhood table, and spent the past 64 years seeing and enjoying them while visiting my mother each year. Now that she is gone, my sister and I are choosing which items we each want and plan to sell or distribute the rest of her possessions.

But here’s the interesting part; I’ve found that when these objects are placed in my home, everything about them changes. My discovery is that for most items, their previous place in my mother’s Mandala of meaning dominates their place in my own. Separated from the web of relationships with other objects created by their placement within my mother’s rooms, the items suddenly seem different. I find myself only able to connect to the deep feelings I formerly felt for each by visualizing it in its customary place in my mother’s home. Isolated from her Mandala, the lamps, chairs, tables and the rest just seem more like “things” – my feelings about them are smaller.

What has been most surprising is the way these cherished objects, each one part and parcel of my mother’s long life and of my own, cannot really stand apart from her Mandala and retain the depth of meaning they once had.

Knowing all objects lack inherent meaning is one thing; realizing and feeling that lack is powerful, disorienting and something altogether different.