Before movies there were dreams, the experience of being simultaneously involved while impassively observing events and emotions displayed on mind’s internal “screen.” In many ancient cultures dreams played a pivotal role in individual and social life. For Australian Aboriginal peoples, Dreamtime is considered the greater reality and our waking state the lesser. For the Ancient Greek seers, soothsayers, sages and fortune-tellers dreams were an indisputable message about gods, truth, and actions in accord or discord with a higher reality.

Freud and Jung, founders of western psychoanalysis, also considered dreams an essential part of understanding human drives, impulses and behaviors. The interpretation of dreams accompanied their introduction of the theory of the sub-conscious, a psychological realm hidden from conscious mind which none-the-less guides and affects feelings, thoughts and actions. Not coincidentally, psychoanalysis emerged at the same time as the first moving pictures around 1880. Movies, in that sense, became the explicit presentation of a particular type of experience which had formerly been only available in dreams.

Though staged drama has a long and storied history in human society, it is a live-action event taking place in three dimensions. As such, it has more in common with conscious, everyday life than movies. No matter how good the actors or how sophisticated the staging, each viewer knows the events are happening in real time, performed by real people before an audience, also real. In this sense, it’s like going to the supermarket, but scripted. Movies and dreams, on the other hand, are not live events peopled by real people; they are acts of imagination.

The character of the experience of dreams and movies are quite similar. In both, images, sounds, and emotionally stimulating events are presented which are beyond one’s control. The movie-watcher and the dreamer both remain physically passive while experiencing a wide range of visual and emotional content. In both, the visual character is dominant and “screen-like” as distinguished from a live, three-dimensional performance which can be interrupted by real events. Neither dreams nor movies are subject to viewer control, though some “active” or “lucid” dreaming techniques are said to place a measure of control to the dreamer.

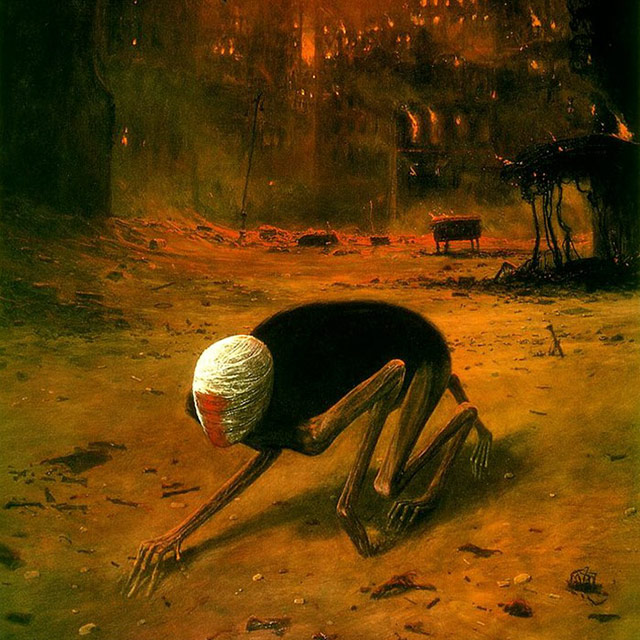

Judging by the content of current movies, their dream-like role as expressive outlets for the sub-conscious is increasing. Just as dreams can contain fantastic events and effects which defy physics, science, experience or logic, so too do many movies today. The power of special effects computing has accelerated this trend towards the fantastic, bringing the power of sub-conscious dreaming to new cinematic heights. Of note, of course, is that a movie is not a dream; while watching, we voluntarily submit ourselves to content created by others who have collaborated on the creation of a cinematic collective dream.

Movies have been with us long enough to have now become elements within our sub-conscious dream life. The images, sounds, characters and locations in watched films are now included in our repertoire of personal content, establishing themselves as shared social archetypes available for use. Dreamworks, the movie corporation started by Spielberg (“Spielberg” means “mountain of play” in German), Katzenberg and Geffen, is an explicit acknowledgement of the connection between movies and dreams.

Luckily, the human sub-conscious is not bound by corporate copyright law. Our dreams remain our own mystifying, quixotic, jig-saw puzzles of meaning. Sleep well.