The CEO of Cambrian, a biotechnology company, wants to upgrade the human race. His plan to is to make genetic engineering available to everyday people in a process he calls “democratizing genetics.” In homage to his namesake, Austen Heinz of Cambrian might someday appear in 57 varieties! As reported in the press, he is one of a growing number of entrepreneurs eager to exploit the abilities of technology to alter the human genome.

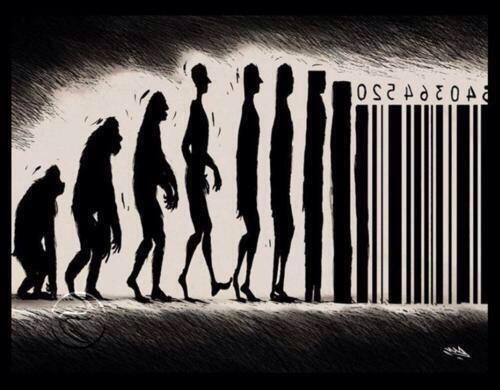

Our love of technology makes his plans all the more plausible. We readily accept and adopt new technologies before asking and answering key questions: What problem does this new technology solve, who does it benefit and who does it not? As author Neil Postman observed, we have entered the age of Technopoly, a period of human history in which technology dominates culture, and in fact, becomes culture. To the likes of Heinz, humanity is simply culture in a “petri dish.”

That such plans contain risk, as do all new technologies, is not new. Each new technology disrupts the effects of a previous technology, making it obsolete, enhancing it, retrieving its forebears, and ultimately becoming so dominant that it brings about the reversal of its own effects. History of the past 500 years is largely the history of technology, but never before has technology made alteration of the human genome so easy.

Our physical evolution has slowed to a near stop for several hundred thousand years, replaced by psychic evolution of imagination, creativity and invention. Virtually all technology is developed as an enhancement of human senses and mechanical functions. Nonetheless, the misguided eugenics movement of the early 20th Century, for example, attempted to influence the physical course of human evolution, informed by methods of mock-science. It is little known that Nazi Germany only adopted its aggressive eugenics program after witnessing widespread implementation of eugenics in the United States, where sterilizations were performed in thirty states to prevent reproduction of “inferior” people, largely African Americans, “criminals” and those deemed mentally ill. The promotion and funding for this was provided by none less than industrialist John D. Rockefeller and only ended in 1963.

Mr. Heinz believes people are already “engineering” offspring in their selection of mates, and that his technology will simply enhance this natural capacity. Thus a choice of blue eyes and blond hair, in his view, is nothing to be alarmed about. His entreaties sound eerily familiar and remind me of the script for Jurassic Park in which John Hammond, creator of the park, explains the logic of his reintroduction of dinosaurs into modern times. It was a Hollywood movie, to be sure, but we all know how it turned out. Faith in technology approaches the level of religious belief – Scientism – and the acceptance of deep mythology which confers its own “creation theory.”

Though we can readily see the many problems created by technology we believe that their solutions reside in yet more technology. In a sense, we have created a technology-based social echo-chamber in which cause and effect have been so effectively accelerated as to be indistinguishable. Accordingly, there is no time for true reflection on the wisdom or folly of our technological decisions; we are carried by their currents and set adrift on the deep ocean of the future with no rudder other than blind faith. Perhaps we can create Heinz’ new humanity on the Pacific’s floating islands of discarded plastic.