There’s nothing that says civilization better then concrete, the perfect word and substance to encapsulate the evolution of human society.

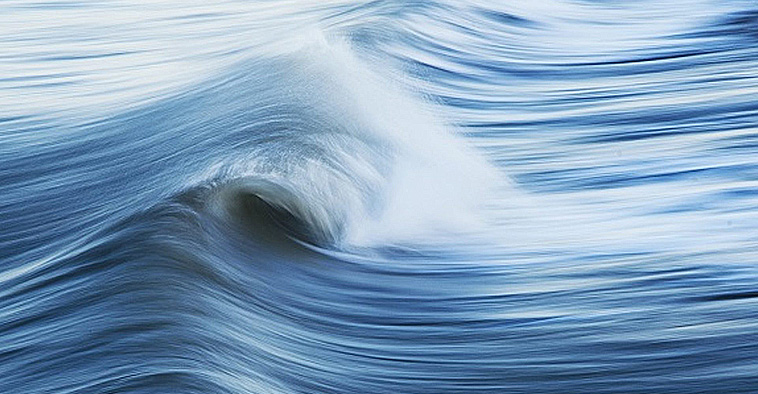

Humanity’s Paleolithic experience, perhaps 500,000 years long, was fluidic – sensorily and intellectually in harmony with nature’s analogical cycles and rhythms. The analog is the world of continuous, informational waveforms; our senses are attuned follow their peaks and valleys, and our brains can resolve their information sufficiently to generate actionable responses. When our eyes are open, for example, we receive a continuous stream of light wave information; our ears are always “on” and ready to receive the sound waves that reach them. In the same way, the analog world is also always “on,” providing a continuous stream of information; there is no “off” switch.

The past 10,000 years, however, wrought change as humanity increasingly moved from the realm of the senses to the realm of the intellect. The Neolithic revolution – metallurgy, agriculture, cities, armies and all that we think of as civilization – induced the solidifying of both thought and action. Our conception of ourselves, the world, and the universe became concretized, filled with fixed explanations and narratives which quickly solidified into rules, dogma and patriarchal social structures. When the ancient Egyptians developed concrete for mortar by adding volcanic ash to gravel and water, the world began a major shift, a shift that manifests today as digital.

Unsurprisingly, the difference between analog and digital reflects ways in each of our two brain hemispheres function. The right hemisphere leans analogical, experiencing the world in an connected, totalistic way, ie: fluidic. The left hemisphere leans digital, experiencing the world in a separated, categorized, named and ordered way, ie: concretely. According to neurologist Ian McGilchrist, in The Master and His Emissary, our two hemispheres exert an inhibiting influence on each other and optimally establish an equilibrium between them. For most of human existence, the right hemisphere of connection dominated; during the past 10,000 years that dominance shifted, and today the left hemisphere of separation dominates, having fragmented, reorganized and civilized human reality through written language, moveable type, uniform bricks, interchangeable parts, and so forth.

Our left hemisphere’s dominance is suitably represented by cities, civilization’s expression of rigid, fixed structures and social control. As the quality of structural concrete improved, so its use expanded. It is now the most widely used building material in the world and its manufacture a major contributor to global CO2. As concrete thinking began to dominate, rigid systems of male-dominated organization manifested; improved technology was directed to weapon development to enforce systems of social control.

With the discovery and deployment of digital technology – continuous waveforms of the analogical world instead divided and re-presented as separated, fragmented and numbered blocks of information called “bits” – the transformation from fluidic to concrete took a great, or perhaps terrible, leap forward. Using “bits’ as building blocks, our civilizing left-hemisphere is constructing a digital representation of itself, increasingly subordinating our right-hemisphere’s fluidic, analog experience of the world.

The presentation of the analog world is immediate and intimate; the re-presentation of the digital world is manufactured and distanced. Accordingly, longing for lost intimacy is a hallmark of civilization, even the intimacy of violence. As the left hemisphere dominates, our right hemisphere continues to seek its natural analog connection and expression. The greater the fragmentation of concretized thinking, the greater the desire for connection; the fluid expression of our analog selves refuses to be silenced.

right on, larry. reminds me of fritz perls’s suggestion for sanity: “lose your mind and come to your senses.”

cb

Well, this time, I completely disagree. I see no reason to think paleolithic peoples were more focused on fluid aspects of experience than the permanent (mountains?, oceans?) or, particularly, the recurring ones. And, besides, fluid situations can be a very difficult problem.

I tend to believe, one way or another, that our ancient ancestors were as short-sight, prejudiced and benighted as you and I.

I think you and I are thinking of different notions of fluid. My frame of reference is an openness to the fluidity of sensory experience, the awareness that does not require thought, and certainly not complex conceptual thought. A mountain is not a permanent thing, but an ever-changing panorama of changing colors, seasons, and relationships. Check out the work of John Zerzan, and his research into civilization and how it has altered human experience, thought and feeling.