From the smallest animal to the largest, hunger, the first and strongest drive to assert itself, underlies the substance of animal behavior. Sensory functions – smell, sight, touch, hearing and taste – all support the search for food, and their humble origins may well lie in that pursuit.

Some animals are carnivores, exclusively seeking out and consuming animal protein. Predators actively hunt other living animals and insects. Non-predatory carnivores get their animal protein by scavenging the corpses of dead animals, the remains of prey killed by predators or the carrion of animals that have expired naturally. In either case, the hunt for animal protein to eat is a constant imperative and impels physical movement in furtherance of satisfying hunger.

Other animals are herbivores that consume leaves, grasses, roots, tubers, and fungi. Like carnivores, their senses are fully employed for this task to help them identify and eat plant material that supports their ever-present and pressing physical needs.

People are omnivores. As von Meier’s recipe for L’Homme a l’Estragon reminds us, for most of human history the definition of fine dining was eating anything that didn’t eat you first. From raw to cooked: fire became the first kitchen appliance 500,000 years ago. Nowadays, higher intelligence sustains our efforts to satisfy the munchies, generating such cultural metaphors of success as “put food on the table, bring home the bacon,” and “make hay while the sun shines.”

Agriculture, an act of delayed gratification, requires seed collection, soil preparation, water provision, cultivation, harvesting and many months of focused activity before farm products can be eaten. Raising poultry and livestock, similarly, is an activity that postpones consumption until animals are large enough to slaughter. Providing food requires elaborations of economy; in some sense, the entirely of commerce – creation of money, banking, lending, investment, and accounting – are instrumentalities devised to satisfy our appetites.

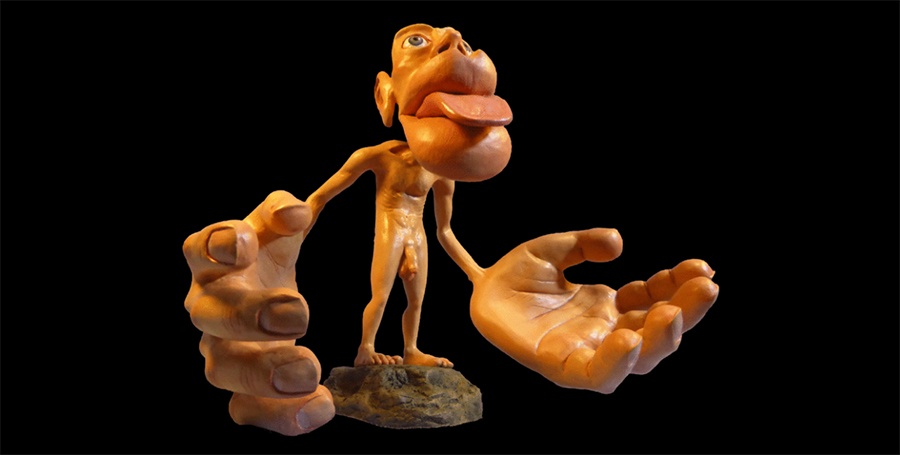

Animal hunger and its satisfaction – craving and satiety – form the simple basis of hand-to-mouth human society. Along with clothing and shelter, food (including water) is part of the triad of basic needs of human survival, but of the three, food is the most pressing. “Grasp, Cling & Consume” is our motto; notably, sensory portions of the human cerebral cortex devoted to hand and mouth are disproportionately large, as pictured in the sensory homunculus above.

Our mammalian oral fixation begins early, and we employ a range of psychological gymnastics to rationalize it as we age. The panoply of human social and personal behaviors are all connected, in their own, sometimes subtle ways, to the satisfaction of desire.

In teachings, from Buddha’s Four Noble Truths to Bataille’s Theory of Religion, desire – for food, wealth, and power – is explained as a response to fear, including the primal fear of hunger; grasping and accumulation are employed to protect us from fear. In order to support accumulation, we’ve developed instrumentalities of dominance and control; laws, enforcement, courts, prisons, armies, and violence are all established towards this end.

Satisfying the hunger of over seven billion hungry people, it turns out, appears to come at the cost of earth’s living systems: rain forests destroyed for farming, ocean wildlife depleted, and human industry deployed to fill bellies. With the arrival of the human species and its capacity for imagination and planning, the billion-years-plus ecological balance of earth’s animal and plant population has been lost.

It’s a tough fact to swallow: we are eating our way to oblivion.

Larry:

Could you further clarify how you see the ecological imbalance between the animal and plant population has been LOST ,please?

jim bohar

Nice essay Larry. I always find it remarkable that, in discussions on nearly

all the woes of modern man–from warfare, climate change, and poverty to caloric deficits and want– the reality of overpopulation as the cause is seldom mentioned.

Keepum Gessen!