Chapter Nine

During the twenty years botanicus has roamed the forests of Nova Scotia, set loose by Pierre Gittleman to repopulate a changing planet, their tribe has slowly grown from an original four individuals to thirteen. Those four consisted of Jens, Saha, Kaya and Karma, raised by Pierre and except for Jens, so named in honor of his father Leonard and the Buddhist teachings he treasured.

Jens, the first born of the four, remained unnamed until he himself could speak. “Jens” was his own invention, an attempt to mimic the name Len, the very first of the botanicus species created by Pierre, Pierre’s devoted aide, and now himself forty years old. Next came the girls Saha, Kaya, and finally Karma, another boy. Together they filled the Gittleman home nursery and were raised into late adolescence.

Caretaking of the babies mostly consisted of physical contact and vocal communication; able to feed on sunlight, neither food nor milk was necessary. No cries of hunger emanated from the Gittleman nursery. Len, the first botanicus, was the primary caregiver, and nurtured, comforted, and played with the children; Pierre participated regularly as well, particularly when it came to matters of learning. Naturally intuitive and empathic, well-attuned to each other and the world around them; not driven by hunger nor the drive to satisfy it through aggression or greed, the young botanicus plant/animal chimera rarely cries from discomfort, and when tears otherwise appear they’re either of joy or in response to perceived suffering, of botanicus or otherwise. And unlike the children of Homo sapiens, botanicus children are generally quiet.

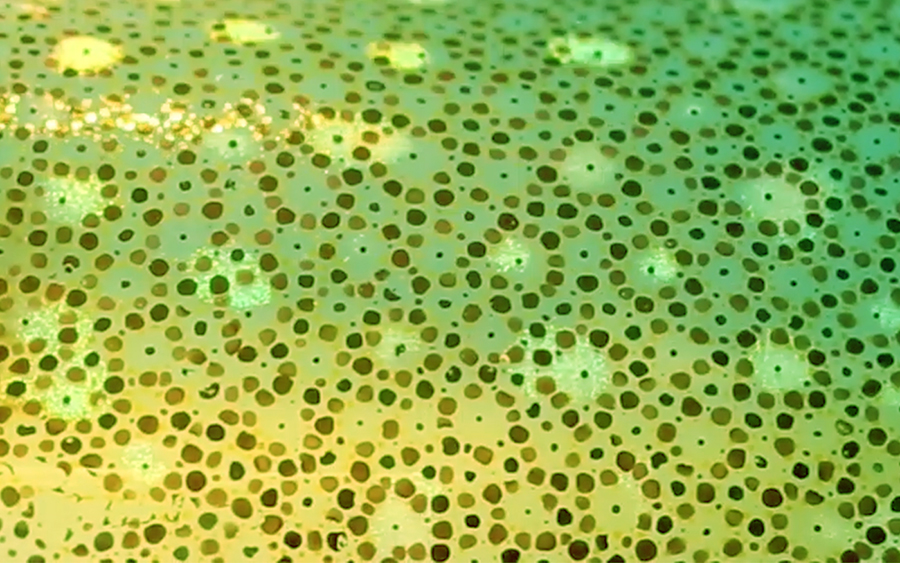

Their quiet nature is a by-product Pierre’s genetic engineering; the inclusion of chromatophores derived from Cephaloid octopus enable botanicus to communicate visually through skin color and pattern changes. Different emotions produce hue oscillations, varying in intensity and frequency with the character and strength of the emotion. Thus, from their very beginnings the children rely upon visual perception of skin changes as a primary mode of relating to each other; words and language come later, but when speaking abilities arise, they do so very quickly.

In general, botanicus are even-tempered, almost serene in aspect. The constant flow of sensory information, less mediated by the brain’s left hemisphere and an increased lateral asymmetry favoring the right hemisphere, contributes to botanicus’ continuous sense of wonder and fascination with the world. This instills them with a natural awareness of totality, interconnectedness; the absence of continuously having to hunt for food provides an enhanced sense of open rather than closed attention. Devoid of predator impulses, the mind of botanicus naturally gravitates to symbiosis and collaboration.

In raising botanicus children, particular attention needed to be paid to protecting their infant skin from harsh, direct sunlight and providing time for the chloroplasts to fully develop and mature. As babies, botanicus skin begins a pale color, but with a distinctive greenish tint. With gradual exposure to sunlight over several weeks, including protection from sunburn, their skin becomes deeply green, darkening with age. Accordingly, growth during the first few months is slow, and nearly all of it is spent in sleep. At about three months, once the skin is fully photosynthetic, the rate of growth accelerates markedly and botanicus infants overtake the developmental stages of sapiens.

Few health threats challenge botanicus babies, the greatest of which are mold infections. Given the chemical composition of their skin, if left too moist for too long, a sooty, black mold spreads quickly, reduces photosynthesis, retards growth, and can be fatal. Pierre learned this the hard way, and also that the health of such infants requires good air circulation and early exposure to filtered light. As time passes, the skin becomes less vulnerable to mold, and by adulthood that risk is marginal, at worst. Physical maturity arrives early, around the age of nine or ten; by that time, botanicus reach their full stature and sexual maturity follows soon after.

How long a lifetime botanicus would enjoy remains unknown to Pierre. The absence of digestion as a primary metabolic activity, Pierre assumed, would increase lifespan; digestion creates a host of substances, some toxic and damaging, as it breaks down consumed food for absorption into the body, and the process of oxidation is itself, Pierre understood, closely linked to the process of aging. How long botanicus might live is undetermined, and it could be far longer than the lifespan of sapiens.

Like any children, the four raised by Len and Pierre varied in temperament. Curious and precocious, Jens was quick to bond with Len and to respond to Pierre’s lessons. As is any oldest child, he was the beneficiary of a great deal of attention. Second in line, twins in the sense that they were “birthed” on the same day, were Saha and Kaya, both females. As the first of the female botanicus, a fair degree of uncertainty accompanied their arrival; Pierre had taken great pains to reduce the physical differences between sexes, but how that would manifest into maturity was uncertain. The twins, much as has been observed with Homo sapiens twins, enjoyed a remarkable degree of compatibility with each other, at times as if they shared a lateral, almost symmetrical mind/body connection. As they aged, their color pattern changes often were synchronous, as if they shared one body.

The last of the four was Karma, a male, endowed with a decidedly distinctive personality and affect. Karma, unlike the others, was emotionally subdued; his color changes did not emerge as early as did his siblings’ and were far more subtle. At the same time, his verbal skills presented themselves far earlier than those of the others, and his gifts of abstraction and story-telling prominent. After examination and testing, Pierre concluded that Karma’s left hemisphere was as active as his right hemisphere, not what Pierre had planned. It meant that Karma, which translates from Sanskrit as “action,” was to have a distinctly different take on reality than his brother and sisters. What, exactly, those differences would mean to him, the group’s dynamic, and its future social structure was unclear, but Pierre concluded that given the vagaries of chance, variance in personality and style was inevitable, and it’s effects uncertain.

Len, of course, cared for the children more comfortably than Pierre; he shared, after all, their genetic makeup; he looked like them. With their arrival, Len’s color shifting and patterns revealed themselves to be primary tools of nurturing and comfort, and while holding one or another of the children, their patterning and sequences would seem to flow from one into another, almost seamlessly. Their intonations, the cooing, melodic songs, would synchronize as well, an effect that Pierre found curiously relaxing and comforting himself. He would, while listening, often drift into a meditative trance, only to discover than an hour or more had passed as if it were only a minute.

The sound, “AOB,” intoned slowly as AhhhhOooooBbb, reminded him of the way his father, Leonard Gittleman, chanted each morning. It seemed to have spontaneously arisen between Len and his charges, but what its use, value, and future application might indicate was unknown to Pierre. He found it pleasant, however, joined in from time-to-time, which helped him bond with the children, and curiously, deepened his own sense of comfort and connection with the tumultuous and quickly changing world around him.

I interviewed Bucky once and had to ask him only a single question; he responded with an hour’s discussion. The line I remember best was his remark that “I can build you a house for $25,000 and deliver it to your door.”

Go Bucky.

Lucky you. I heard him speak, but that’s as close as I got to him.

LB