Why are we so war-like, or more honestly, why are men so war-like? War-like behavior among wild chimpanzees is a documented fact. Naturalist Jane Goodall observed that when a group of chimpanzees breaks off from a larger troop, the two alpha-male groups get into conflict. Males, and some females, make organized forays into the competing group’s territory, and if they encounter a vulnerable male, will viciously attack and even kill it.

Now, human beings are not chimpanzees, but we often regard strangers with suspicion and respond with overt hostility. Within the animal kingdom, aggression is common; many animals are predatory, after all, and among them human beings are the world’s apex predators. Some species of tropical ants make organized forays in search of food, but only humans develop and wield advanced weapons against their enemies, not to eat them but to dominate them.

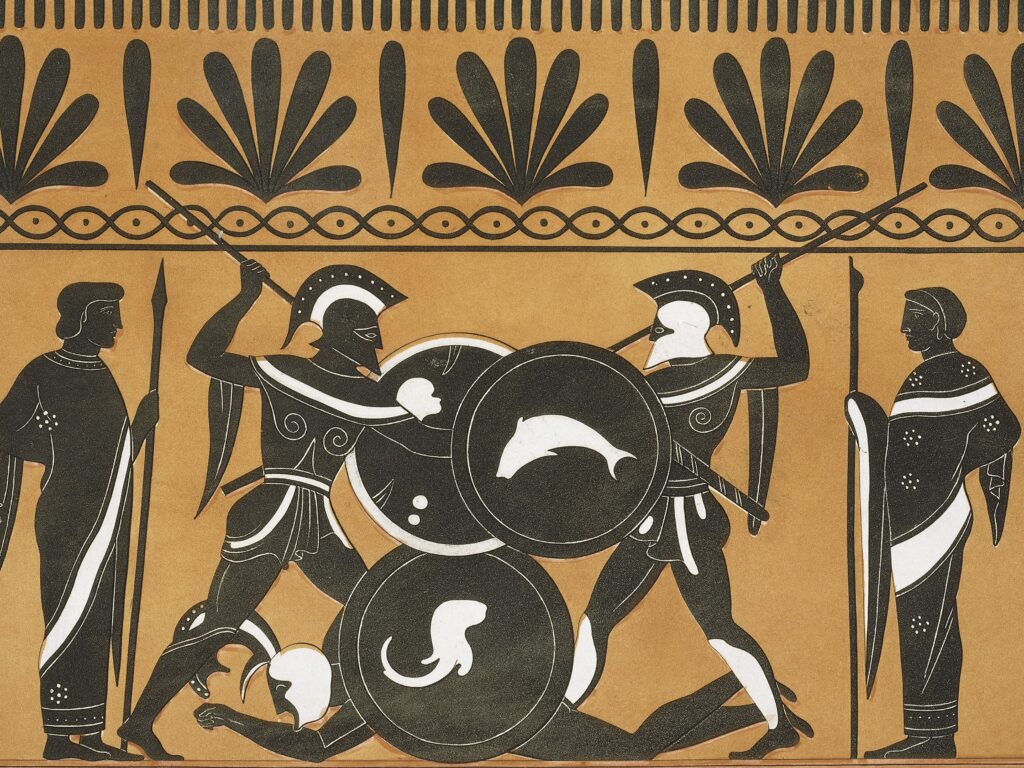

So entranced with warfare are we that culture, both ancient and modern, is replete with epic poems, songs, and drama about war. Admittedly, the documented history of the world is male history, and thus not surprising that war plays a major role in it. Many men love the idea of war, if not its actuality. Homer’s Iliad, originally an elaborate oral history of the Trojan War, is a template for war histories thereafter. The Greeks were an honor-based society, honor in the sense of prestige, tribute, and treasure, and the acquisition of honor fueled terrible acts of violence, exquisitely recounted in gory detail in Homer’s epic poem.

While the idea of honor has shifted from tribute to respect over the ensuing thousands of years, the honor of war remains high on its list of justifications. That cycles of murderous revenge are transformed into glorious tales of honor illustrates how narratives promulgate the fiction that war is necessary, and even good.

For thousands of years, war and conquest have been considered a vital engine of civilization, essential to economic and cultural health. With the rise of modern nationalism in the 19th and 20th centuries, warfare reached a fevered pitch as competing armies vied for global dominance. Unaccountable millions died, often for nothing, as in World War One. Investment in the weapons of traditional warfare mushroomed.

For a while, the presence of nuclear weapons and their use put a damper on war. Destroying all life on planet earth seemed too high a price to pay for honor; nuclear weapons became a deterrent rather than a tool of war. Ironically, the possession of nuclear weapons has now reinvigorated traditional warfare, not deterred it. Those nations with nuclear weapons saber-rattle but dare not use them and know no other country will use them either; only a madman or terrorist would. In the meantime, artillery, tanks, troops, bullets, rockets, bombs and traditional explosives have never been more popular. Unusable, nuclear weapons have made traditional warfare good again.

So here we are. Ukraine is fighting for its honor against Russia, which is also fighting for its honor. Israel’s honor is at stake against Hamas, which fights for the honor of the Palestinians. Taiwan is prepared to defend its honor against the People’s Republic of China; North Korea and South Korea’s honor are on the line, and so on and so forth. Like reciting some modern-day version of Homer’s epic poem, the world continues to herald the necessity of war while the innocent are bathed in its blood and gore. Honor indeed.

When it comes to global warming, pandemics, hunger, air pollution, and food-chain issues, one of the core problem is seldom mentioned or addressed: over-population.

Of course there are many causes for warfare, but it does temporarily and locally solve (for a short time) one problem that birth control should have and could have prevented.

That’s very Malthusian of you Robert. Population projections show a decline and leveling off over the next 50 years. Developed countries are in a sharp decline; there are so many vacant houses in Japan that you can buy a million dollar home for a dollar. Entire villages in Italy are empty.

Timely article Larry. How long, if ever, will we grow up as a species? Hope you are well.

Good to hear from you Michael. I’m hanging in there at 75. If your question is, as a species will we ever outgrow our collective and individual neurosis? As you know, the answer, regrettably is no, we will always be trying to cope and manage with it. But, you know that!