Of the elements of the Industrial Revolution (1760-1830), the development of interchangeable parts was among its most significant. Not simply the efficiency of building machines was affected; workers were reduced to interchangeable parts, too, which greatly enabled the growth of capitalism.

As economist Karl Polanyi pointed out in his remarkable book “The Great Transformation,” the fiction of “labor,” i.e. the reduction of worker effort into a calculable “thing,” was transformative, and emblematic of the power of capitalism to dehumanize life and society.

For roughly four or five hundred years prior, the economies of Western European society was Medieval, a system of craft guilds comprised of master artisans and their journeymen. Local in scope and subject to regional rules and customs, guilds satisfied the product needs of local communities. More significantly, they provided a sense of place and purpose to people who would spend a lifetime perfecting specific talents and producing essentials for their community such as shoes, tools, and furniture.

The rise of capitalism and its elevation of wealth accumulation as a sign of God’s favor, a development enabled by the Protestant religious reformation initiated by Martin Luther and John Calvin, doomed the Medieval guild system. For workers, a secure place in society disappeared with it; now interchangeable parts, the abstract concept of “labor” was a major step in dehumanizing people. The Industrial Revolution rendered that transformation unstoppable.

Among other effects, the decline of Medieval guilds effectively converted interdependent communities to mere engines of commerce; traditional rules of morality that had classified greed as one of the seven deadly sins were discarded. Competition replaced cooperation.

Yet another influence on the rise of capitalism was the Renaissance (1400-1600), what we today view as the flowering of culture and invention. As wealthy merchants began to support artisans, their influence increased. For example, the wool merchants of Venice provided funding and solicited bids to create the Baptistry doors of the Florence Cathedral, awarding the contract to artist Lorenzo Ghiberti, who developed a casting technique more economical than those in use at the time. Art became business and birthed the dawn of artistic celebrity, a powerfully dominant phenomenon still.

When it comes to the activity of dehumanizing people, war is its perfect instrument. Weapons of war – and no less than the celebrated Renaissance artist/inventor Leonardo DaVinci designed many, including tanks, scythed chariots, multi-barreled cannons, crossbows and catapults – fueled the expansion and power of City States. Today, weaponized Nation States dehumanize war’s innocent victims by euphemistically classifying them as “collateral damage.”

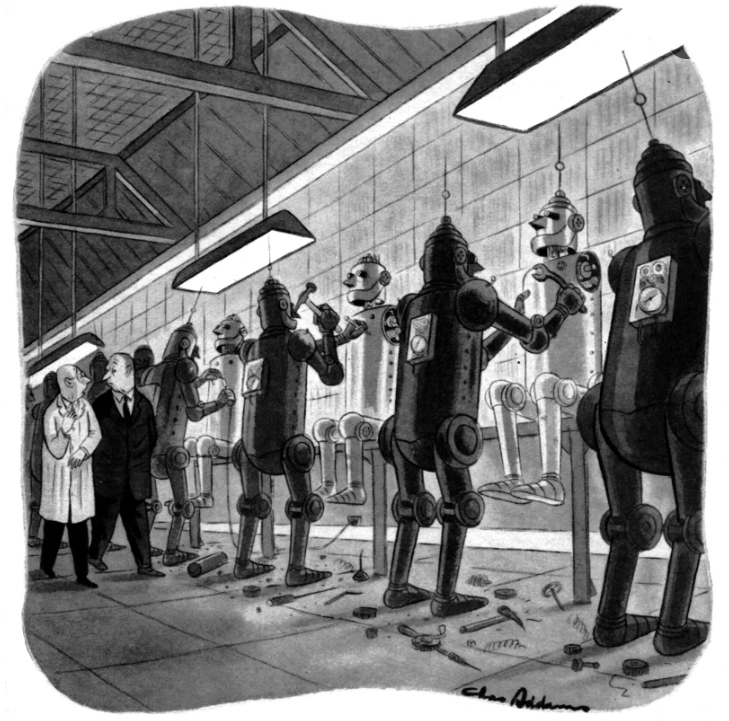

Ironically, in our digital age we’re trying to humanize Artificial Intelligence while simultaneously dehumanizing the workplace and society. Faces, voices, and entire personalities are being cloned by AI software for economic exploitation. Meanwhile, multiple job classifications are threatened as machine intelligence replaces people. Not just technical jobs are being eliminated, but jobs that customarily require human-to-human interaction. Reduced to objective data points in computer server farms, people are better tracked, classified, graded, and targeted by the engines of commerce than ever before. It is capitalism above all else that insures the rise of AI due to its potential future in making lots of money.

Viewing the world as something to be used, its utility, is a hallmark of human activity. It is precisely this inclination that’s propelling the deployment of advanced machine intelligence, which as it improves will undoubtedly conclude, as humanity often has, that people are things to be used.

Your wisdom and intelligent analysis, simply and elegantly encapsulated into a few dense sentences and paragraphs, is breathtaking and greatly appreciated.

Thank you!

Damn, Larry, I think what this means is I’m still stuck in Medieval times. I hate using humans, though in industrial society it’s impossible to avoid, and I value craft and labor. The good thing about AI is it will reduce demand for using people, maybe we can go back to a guild system of craft to fill our long days of idleness. Or sign up for classes in the Devil’s Workshop!

Unfortunately, I think AI will conclude that using people is just fine. It’s all about the teleology of the system, its purpose. If its purpose is increased corporate profit, then using people to further that will happen. People can be used in various ways, not just as workers, but as consumers, and as consumers, people can be manipulated etc. Imparting human values into AI will not make AI more compassionate necessarily; I don’t think an algorithm for empathy will do the trick.