When water becomes hot and agitated enough, it becomes a gas. When solid iron is heated to 2,800 degrees, it becomes a liquid. These are examples of what physicists call a phase transition or shift, a radical restructuring of matter from one form into another.

While the actual transformation can be sudden, it is possible to observe the signals leading up to a phase shift. For example, when heat is applied to a pot of water, the first signs of change include small bubbles that form on the bottom of the pot. As the heat continues, the water molecules become more excited and the bubbles increase in number and begin to rise quickly to the surface. Reaching 212 degrees, the entire pot of water begins to boil, the contents assume a roiling chaotic nature, and the water becomes a gas in the form of steam. Comparable effects can be seen when melting iron – when heated it progressively changes color from black to red to white, and then turns into a liquid as the phase shift occurs.

Chaos in a fluid medium displays what is called turbulence. Turbulence is the spontaneous arising of distortions and deformations of liquid flows due to the effects of speed or heat. Given enough speed, a liquid will begin to exhibit turbulence, particularly if there are obstructions or deformations in its container, though speed and heat alone are enough to create turbulence. As turbulence increases, counter flows, feedback loops and visible signs of disorder emerge. So it is with America’s monetary system, which subjected to extraordinary volume, speed and pressure has undergone a radical phase shift borne of chaos.

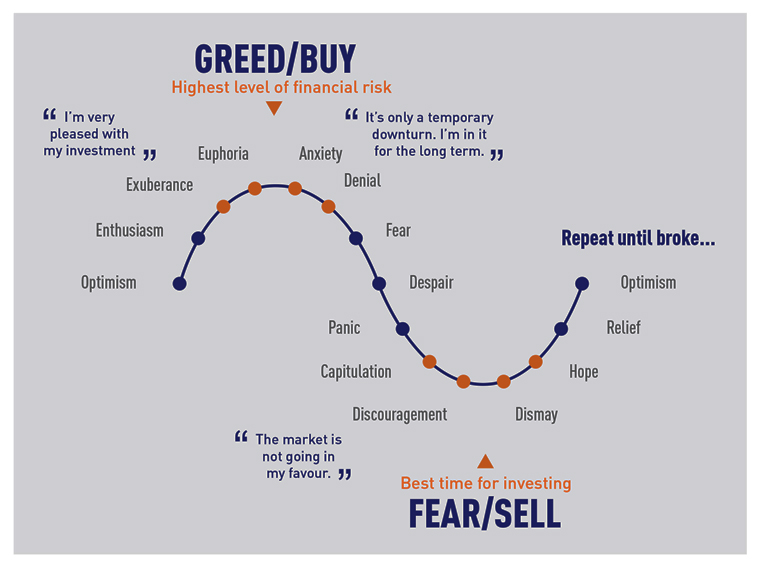

Turbulence in the nation’s monetary flow is analogous to the effects of speed and volume in the flow of water. A monetary system must flow (hence we call money “currency”), and its movement is essential. If money stops flowing, it does not generate investment, interest or profit. If money flows too quickly, however, or if the vehicle in which the money flows is leaky or distorted, turbulence arises. Its signs are frothiness in the markets, what Alan Greenspan once called “irrational exuberance,” and increased monetary inflation pressure. In a “hot market,” stock values begin to swing wildly upward, and the volume and speed of trading and transactions increases rapidly. Without controls on the speed of the flow – “cooling” the market – the system becomes vulnerable to the formation of distortion, investment “bubbles” which tend to burst and a heightened risk of complete chaos.

For the past 25 years, stock market regulation has been considered evil because it slows down the currency of money. This cooling effect has been viewed as a constraint on quick profits, which it undoubtedly is. Under decades of deregulation, those who stood to gain from removing moderating regulations have made uncountable billions, presiding over the greatest transfer of wealth from many hands to few in the 200-year-plus history of this nation.

In the case of Wall Street’s recent crisis, the unregulated heat of greed propelled markets to the point of chaos. This turbulence has led to a monetary phase transition in which the underlying financial assets have changed from something solid into a gas. Having assumed this gaseous state, hundreds of billions of dollars of value have now disappeared into thin air.