I spent last week attending to my ailing 88-year-old father. Generally good-natured and optimistic, he had been laid low by a sudden painful swelling in his right knee, accompanied by weakness, chills and shortness of breath. The combination landed him in the hospital for a week, where it was determined that he was seriously anemic, and suffering from an arthritic-like inflammation of his knee. The infusion of fresh red blood and a high dose of steroids slowly eased his symptoms, and after he returned home I flew in to offer comfort and conversation.

My father is not a patient man, and that makes him a lousy patient. When his body disappoints him, he reacts by getting angry and depressed. That reaction is not unusual; most of us react that way from time to time. This time, however, my father was afraid.

So a portion of the week was spent in conversation about dying and what precedes it. We talked of sudden death and we also talked of living while the body slowly falls apart, while legs or heart or kidneys start to fail or pain sets in. Ordinary activities become burdensome or impossible altogether, like opening a jar of jam or pulling on a sock. Meanwhile, the watcher in us catalogs the ways in which we dissolve. Shame, anger, embarrassment, sadness and frustration all appear, but the most difficult of all emotions that can arise is the fear of death.

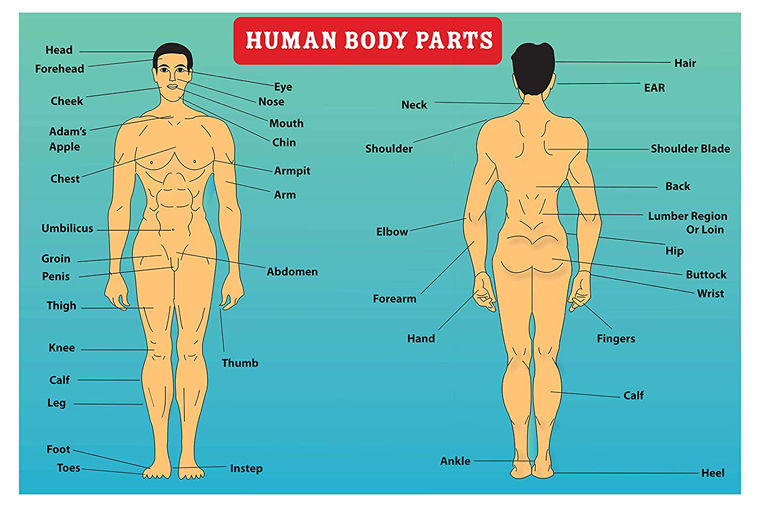

My father, like many of us, thinks his body is like a car. If something goes wrong, we take our body to the shop to be fixed. The doctor kicks the tires, checks the fluids, listens to the engine, and then prescribes new gaskets or a fuel additive to help things run smoothly again. With replacement hips and knees and heart transplants it’s easy to begin to believe we are made of interchangeable parts. But we discussed how this mechanistic view of things only goes so far, how it serves to objectify the body and separates our conception of it from our sense of self.

Where is self found; is it in our head? Perhaps some part of self is in a finger. Surely, giving up a finger, not to mention a foot or leg, is not easy. Should that come to pass, none of us can be certain what will be lost. What then to give up everything? Is it possible to fall apart and disappear and not lose touch with self? Dying begins the moment we are born, and we suffer small deaths every day. Ideas, fantasies, memories all die, are forgotten and disappear; our very cells are not all the same as those we enjoyed last night.

As the week wore on my dad felt better. He began to tell his stories once again. We chuckled and cried and I taught him how to walk with a cane. I knew he’d turned the corner when the discussion turned to politics; talk of death was gently put aside. Early the next morning I flew home.

I called him when I arrived. “I made my own lunch today,” he crowed into the phone. “That’s great,” I replied, “I know you really like it when your tank is full.” There was a moment’s silence, and then we laughed.