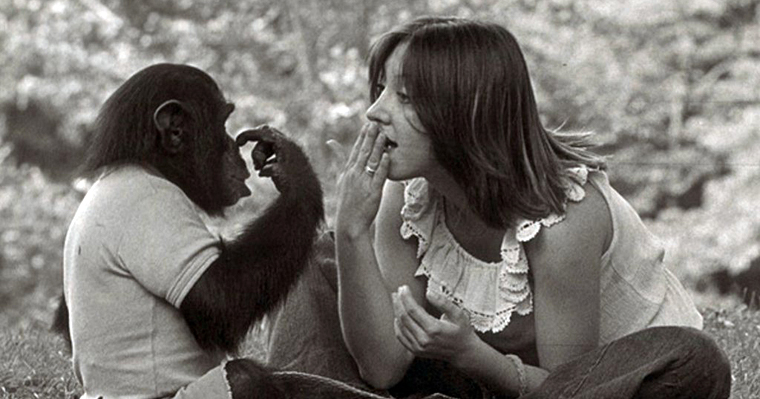

I recently noted the passing of Washoe, the 42-year-old chimpanzee that became a pioneer in human-chimpanzee communication. Washoe was taught to use human sign language and the manipulation of symbols to communicate, and researchers claim Washoe was able to construct complex sentences and engage in abstract thought. She also, like Imelda Marcos, reportedly developed a fetish for shoes.

Animal communication, of course, does not require language, but simply vocalizations, body postures, expressions and gestures. From mating displays to signs of dominance or submission, communication in the animal world enables survival and adaptation. For as long as humans and animals have coexisted, a unique form of cross-species bonding has occurred. Dogs, horses, cats, monkeys and many other animals form meaningful relationships with people, and traces of this history are widespread within our culture. Automobiles named “Mustang,” “Jaguar,” “Ram” and “Cheetah” are but a few of the names we use in acknowledgement of this heritage.

For those of us who have had a pet, the emotional connection that is formed feels natural and shared. Despite the intellectual and behavioral differences, there are many qualities in common between us and our animal friends, not the least of which are companionship, dependency, protectiveness and playfulness. To imagine that these emotional components in animals occur in isolation from deeper mental constructs is absurd. Animals are subject to strong habitual patterns and instinctual drives, but these need not be viewed as entirely replacing some thoughtfulness.

The human capacity for recursive thought has long been considered that which distinguishes human beings from other animals. Recursive thought is that which connects a series of “if/then” concepts, each built upon the concept that precedes it while at the same time retaining the links between. Such lengthy abstract recursive streams of logic can be extended in an almost infinite direction. It seems that sign language has revealed the capacity for recursive thought in other animals. It is worth considering, however, whether we are helping animals by providing them new methods of human-like communication, or simply satisfying our own scientific curiosity while causing such animal subjects great confusion.

Like Washoe did, Koko the gorilla demonstrates a complex and intriguing personality, filled with the expressions of tenderness, humor and even irony. She communicates in sign language about the softness of a kitten and her own feelings of loneliness. Separated from natural relationships with others of her kind, she is a perennial child among humans, treated kindly, but always apart. And having been provided a complex language to communicate with people, Koko also communicates her neurosis. In Koko’s case, she has developed a persistent fetish about nakedness and nipples.

Unclothed herself, it is no surprise that she is fascinated by our removable coverings. This development underscored a lawsuit filed by a female employee who felt pressured by Koko’s keepers to undress for Koko. We certainly can’t blame Koko for this man-made legal and psychological mess and I am not saying that Koko needs the help of a gorilla psychiatrist, but what responsibility do we have now that Koko can communicate in human terms?

In any event, as to the ageless question, “If animals could talk, what would they say?” – in Koko’s case the simple answer seems to be, “Take off your clothes.”