The defining character of the modern age is its relationship to acquiring knowledge: the idea that knowledge is power, specifically power over nature and others. This orientation distinguishes modernity from antiquity’s belief in knowledge as its own reward and wisdom ultimately found “in here” not “out there.”

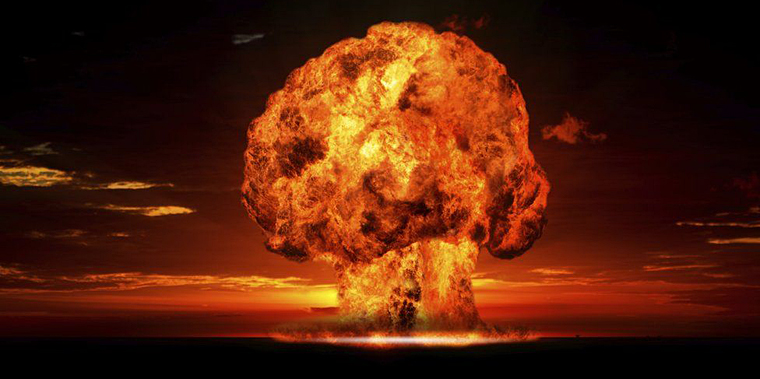

Viewing knowledge as power has transformed the natural world. Knowledge of physics, chemistry and mathematics has accelerated quickly since the 17th century, the beginning of the modern era. Accordingly, both planetary ecology and human society have been radically altered in positive and negative ways by transportation, medicine, agriculture, and communications. Warfare and technology walk hand-in-hand, resulting in ever more powerful weapons of mass destruction, literally endangering all life on earth. At the same time, our understanding of the universe extends 14-billion light years into the past, and at the opposite scale ever more fundamental sub-atomic fields and particles continue to reveal themselves.

Knowledge as power underlies everything about modern civilization. This truth came into sharper focus recently as biotechnology researchers successfully created an airborne and lethally infectious version of a Bird Flu virus for “research” purposes. This event has reignited debate about the use of knowledge, namely is our ability to do something reason enough to do it? In other words, is the power of knowledge worth every risk? Those who answer “no” to this question fear such knowledge will fall into evil hands, but there is a deeper issue at play: saying “no” subverts our conception and attachment to what we moderns call “progress.”

Confronting our attachment to progress places us face-to-face with the basis of our search for power: power over death. Our fear of death propels us to relentlessly seek knowledge to overcome mortality. Thus we perform Bird Flu experiments to create a deadly virus so that we may learn to defeat it. Though we don’t readily admit it, we are so afraid of death we repeatedly invent and overcome our own methods of destruction. Any objection to “progress” feels to us like surrender, yet the materialism of knowledge as power betrays our innate natural wisdom that all things born must die.

The modern path of knowledge offers material transformation that undeniably brings pleasure, but little lasting benefit of true wisdom. Our lives, filled as they are with gadgets, gizmos and out-of-season grapes from Chile, cannot ultimately replace the inevitability of death nor the profound sense of peace and comfort that comes with accepting it. The ancients knew this, and understood that not power, but wisdom itself is the perfect fruit of knowledge.

Long ago I lived next door to an old man, 101 years old. Fred would spend his day sitting in a dark shed splitting wood with a hatchet and a hammer. Fred was deeply spiritual; born in 1868 he’d contemplated knowledge for a long time. One afternoon in 1971, I asked this man born in the age of carriages what he thought about men landing on the moon. “Oh well,” he said in his high-pitched, sing-song voice, “men must have their toys.”

Perhaps playing with “toys” is just the lingering innocence of modern cultural childhood and Bird Flu experiments merely the result of misunderstanding the truth of knowledge. We may yet grow up, but it better happen fast, for we are not playing with toys, we are playing with fire.