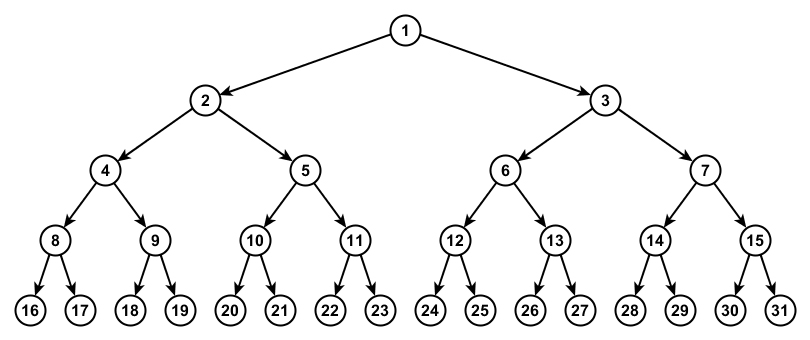

Time can be visualized as a branched structure of causes and outcomes, beginning with interactions between the simplest subatomic particles all the way up to the current composition of the cosmos. All that exists and has ever existed is interconnected by this vast array of branched history. A limited number of branches are visible within each human lifetime; looking back we can see the sequence of life’s events, outcomes which themselves became causes generating additional outcomes.

Despite the continuously increasing complexity of events, each present moment has its seeds in all and everything that precedes it, and thus is always complete, a totality of perfection.

In trying to make sense of our complex existence, people naturally seek explanations for how things happen. Telling and hearing stories is surely as old as human beings themselves. Such explanations are necessarily only partially correct; existence is too complex for any single theory to describe completely. Accordingly, stories and theories vary widely, from tales about the world carried on the back of a turtle, the dome of sky actually a solid curved surface upon which the stars and planets are affixed, the presence of an omnipotent supreme being, all material existence generated from the vibrations of infinitesimal “super strings,” and so on. With each successive generation, new stories emerge.

Human beings inhabit an imaginative realm and use symbolic forms, such as words and pictures, to tell stories to try to convey our wordless internal experience to others. Neurologists have discovered that throughout the brain of a listener or observer a network of “mirror” neurons activate and replicate feelings and movement in response to heard or observed stimuli. This is considered by some as the root of empathy, and accounts for our attraction to various forms of entertainment. We can virtually “see” ourselves within stories told by others, feel their excitement, share sorrow and love.

Having moved beyond stories of gesture and spoken word told “round the fire,” people have created progressively more complex forms of entertainment. Writing and books replaced the vast memory required in the oral tradition: recording and radio extended distance and exposure; photographs captured specific moments in time, and the progression to moving pictures linked each moment of a narrative to the next; the flickering light of television spread stories to every household; the computer and current digital technology brings stories to each individual. In time, entertainment will be transmitted directly to each brain and provide a complete simulacrum of reality.

This raises a basic question: why do we seek ever-greater entertainment? Are we simply distracting ourselves or is a search for truth at play? In some sense a search for play is our truth. Children naturally develop stories, something parents and grandparents know well. Kid’s stories display their incomplete understanding of the world, as, it turns out, do the stories we adults tell, but the stories of children are more dreamlike and unpredictable.

People are seeking and finding entertainment as never before. Entertainment is a major driver of our economy and part of day-to-day life. Yet, the ordinary life of the mind is ultimate entertainment, each arising moment completely fresh and filled with possibility, a perfectly branched totality of constant universal change. Within such ordinary moments perfect boredom can be found; open, undisturbed, self-revealing, readily available.

And to find it? Relax, let the moment go, then let go of letting go.