To uncivilized people the whims of nature surely seemed capricious; their search for meaning behind devastating winds or a great flood gave rise to tales of gods, magic and otherworldly realms beyond the powers of direct human observation. Seasonal cycles, animal migrations, phases of the moon, daily tides, and movement of the heavens provided ground for the roots of human society, and social practices and beliefs established themselves accordingly. In this way sense was made of the natural world, which though still powerful and often unpredictable, appeared to be solidly linked to human culture through its ritual practices of incantation, sacrifice and religion.

Civilization, as Freud noted, has its discontents, but our modern technological civilization is not one might say merely discontent, but crazy. During the past 2000 years, and the most recent 500 years in particular, the experience of the natural world has largely been replaced by immersion in a man-made world, one in which the control and domination of nature has been a primary objective. Though religion, belief in magic and superstition remain substantial forces, they are less arrayed in response to nature than to culture. Fundamentalist movements all share rejection of modernity and a longing for return to “simpler” times.

When it comes to human beings, however, nothing is simple. As the effects of human imagination continue to manifest in physical and metaphysical ways and largely leave the world of nature behind, making sense of the world has become nearly impossible. We no longer look to seasonal animal migration but quarterly financial reports; it’s not the tides we watch, but the Dow Jones Industrials; the phases of the moon no longer get much attention, rather it’s the phases of the economy; the movement of heaven has given way to the movement of Google. To the uncivilized mind our modern times would appear as madness – delusional ravings disconnected from the elemental forces of nature and accompanied by collective and individualized fits of violent homicidal outbursts.

To live in our civilized world requires madness, but we call it sanity. The tyranny of “normal,” a purely statistical function, imposes standards of belief, action and behavior attuned to promoting acceptance of everyday madness. From childhood upwards, technological civilization demands conformity and denial; conformity to our conventional forms of normal madness and denial of the legitimacy of any other idea of normal. Accordingly, those who we label “insane” include many who simply see and cannot endure the civilized madness in which we are enveloped.

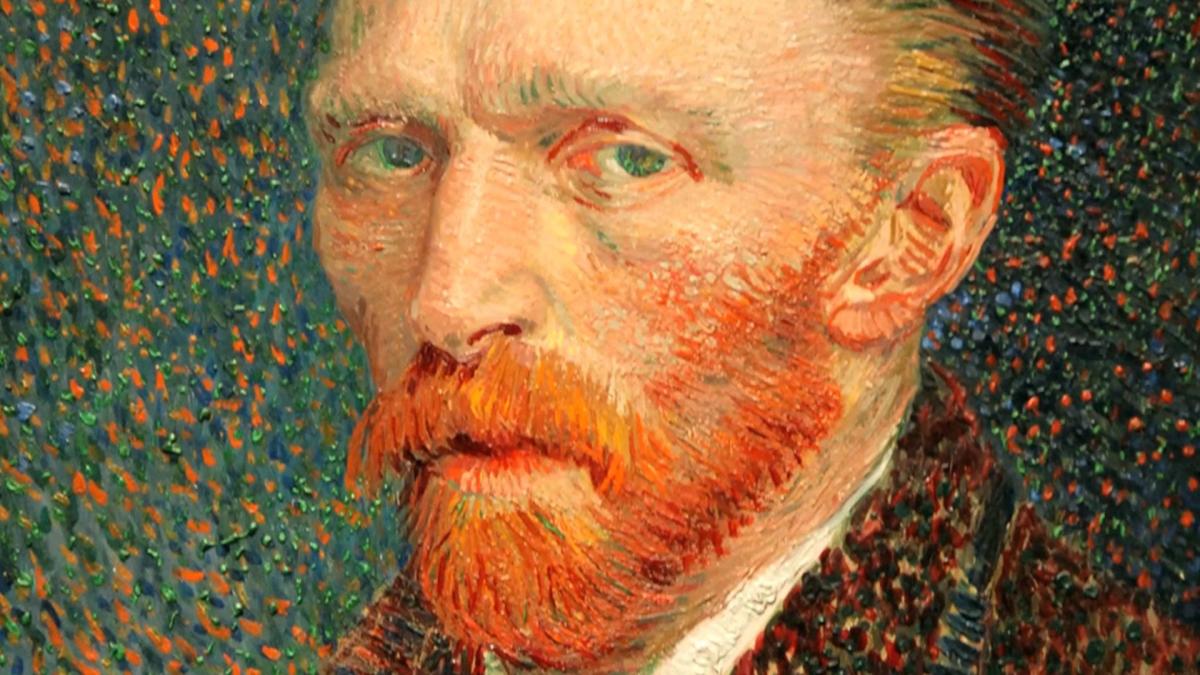

The artist who in pursuit of truth forsakes wealth and fame, the traveling political activist who persistently but vainly holds a sign of protest and the homeless wandering poet who lives by using the discarded possessions of others all share the possibility of basic sanity. Though by modern standards insane and living outside of the boundaries of “normal” they (and by extension each of us) can, as through a magnifying glass, see society’s madness in greater detail.

The “insane” among us are, like canaries in a coal mine, the first to smell impending disaster of global warming, the spread of high-tech military and nuclear weaponry, untested genetic engineering and the “internet of everything.” What our crazy world calls normal the mad among us call insane and we would best pay attention to their ravings; in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.