We no longer sacrifice human beings in ritual killings for the sake of a good harvest, though given their effects on human health we could view the use of agricultural poisons and pesticides from that perspective. Capital punishment in America, however, which objectively is unnecessary to protect the public from murderers once they are incarcerated, now fills the psychic role once occupied by human sacrifice. Though no longer, as capital punishment once was, a public spectacle taking place in a location accessible to all, we nonetheless invest millions in facilities specifically designed to house those condemned to die at the hand of the state, and widely announce and publicize each execution. The Supreme Court has just this week again approved the use of drugs for executions, and here in California capital punishment may soon resume.

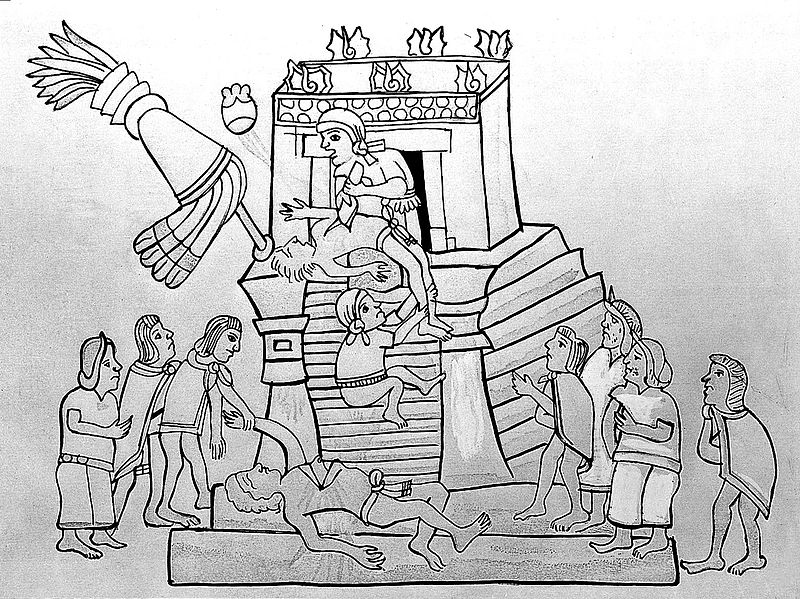

Ritualized killing for cultural reasons was once a wide-spread characteristic of human society. Primitive cultures used ritualized killing in ceremonies meant to satisfy the imperatives of supernatural forces governing matters of birth and death, fertility and rebirth. Religious beliefs and mythology established the link; the Aztec, Mayan and Toltec people of Central and South America had a deeply established beliefs about death. The Aztec zeal for extracting beating hearts from its sacrificial victims, for example, was directly connected to core mythology about the demands of supernatural beings for human blood, which ensured the continued fertility of the “tree of life” sustaining the world.

Early cultures in the Northern Hemisphere also subjected captives to ritual torture and death; observation of nature and its seeming ruthless consumption of life to sustain life inclined these people to develop rituals which reflected their observations. Often such captives were not treated harshly as enemies but as symbolic representatives of a sacred cycle of life and death – clothed, housed, well-fed and spoken to gently while being tortured.

Even Christianity employs a mythology of tortured death before eternal life, sacraments of bread and wine offered literally as flesh and blood, rebirth, and salvation of humanity. The attainment of sainthood included a passage through suffering, often gruesome and bloody. The Inquisition and witch-burning episodes provide other examples of ritual killing explicitly connected to the salvation of the soul.

Nowadays, we house, clothe, protect, feed and provide for the needs – including physical and spiritual needs – of those awaiting execution. The condemned enjoy a special status in segregated “units” under special rules and conditions. We no longer tear the hearts out of living victims, but we do make them stop beating. We’ve used nooses, guns, electric chairs, deadly gas and most recently drug “cocktails” to do the deed. The killing act itself now happens in a highly ritualized and solemn process, intended to be pain free and without suffering.

Though now disfavored throughout the world, 30 American states continue the peculiar cultural ritual of death penalty killing. Only this ritual, say proponents, will properly cleanse society, make it whole and propitiate the blessings of safety and survival. One cannot but suspect that “eye-for-an-eye” dictates from an old testament God are also being satisfied, and in this uncomfortable aspect we share perhaps altogether too much mythology with the ritualized sacrifice performed by our ancestors.

Nebraska is the latest state to outlaw the death penalty, and America remains one of the few industrialized countries to allow it. Perhaps nothing speaks to the evolution of humanity more than the elimination of ritual killing, and we cannot count ourselves modern unless and until the death penalty ritual itself is pronounced dead.