What we call communication – the words and symbols we employ both orally and in written form – strikes me as too primitive to be trusted. Our connections with each other one-on-one or in small groups can include physical contact, but once we get beyond that intimate level, we must rely upon clouds of shared meaning and emotional memory.

Shared meaning is found in “objective reality” – agreed-upon customs, practices, rituals, habits, conventions, values, descriptions under law, cultural symbols and signifiers. Sometimes one person’s notion of objective reality disagrees with another’s; then lawyers, judges and sometimes prisons are needed. But mostly people get by. We cannot read minds, so we rely on a primitive system of grunts and symbols.

Emotional memory is something each of us brings to the present moment. We have witnessed and participated in numerous emotional situations and been forced to integrate them internally and sometimes convey the meaning of them to others. Outside of each other’s skin, we rely on grunts and symbols to accomplish that, too.

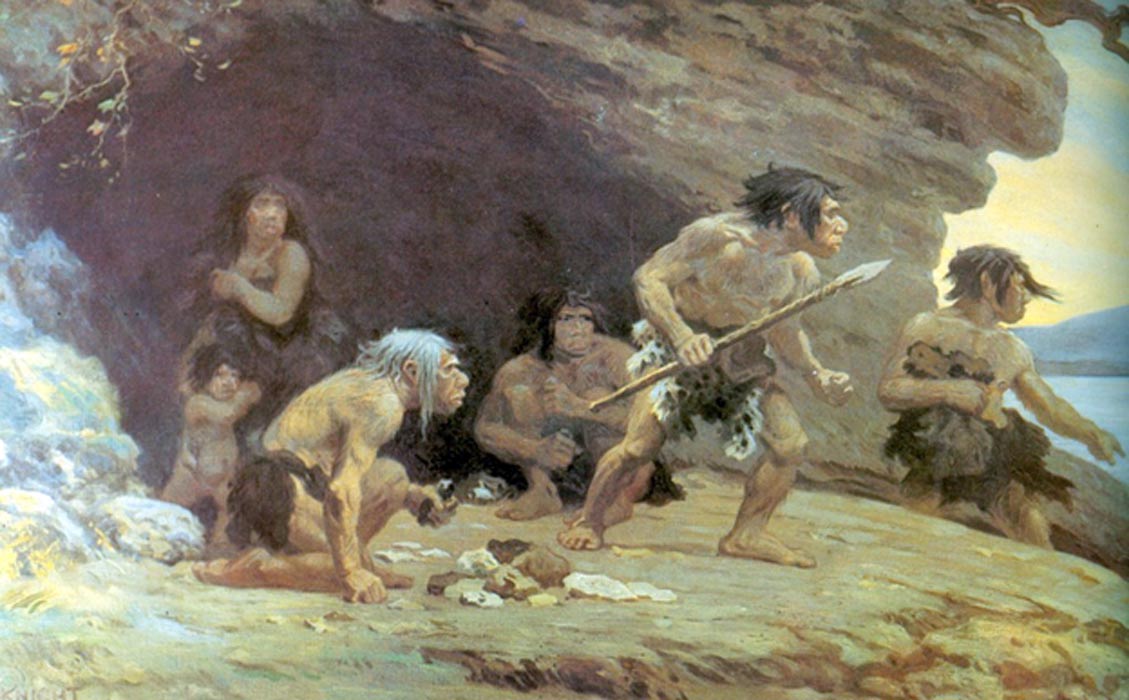

Nobody knows which came first, the grunting or the symbol. They probably were co-emergent, kind of a chicken-or-the-egg situation. The consistently spoken grunt – what we call a word – and a clearly pointed finger comprise a simple language. And before finger-pointing, noses pointed and hoots were made of various sorts and styles. From such simplicity arose the complexity of our first clouds of shared meaning.

When it came to writing, the Chinese developed a system of separate pictographic symbols built upon four “root” families. Knowledge of thousands and thousands of separate symbols was required for literacy in Chinese, and meaning found in their subtle combination; proper pronunciation required years of instruction.

The Western alphabet, conversely, developed not to graphically depict images, ideas, feelings or objects, but to signify the various sounds made by the human voice and mouth: our grunts. Using a small set of 26-characters, an infinite number of sounds, native and imitative, can be signified and represented. Humans have become sophisticated grunting symbolists, indeed.

However, our grunts cannot keep up with our cloud of shared meanings. It has become increasingly difficult to agree on what constitutes objective reality. Everyone has equally become “smarter and better informed,” and though the opinions of billions of us are shared back-and-forth daily, the Internet has become a contemporary “Tower of Babble.” The hooting is so fast and furious it’s impossible to know who to listen to; the competition is fierce and in today’s world the grunter with the deepest pockets generally gets to set the agenda.

The Climate Change Deniers oppose the Climate Change Believers; Evangelicals oppose the Humanists; Supply-Siders oppose the Regulators; Republicans oppose the Democrats, ad infinitum. Everyone has “real facts” and “superior logic” on their side, and everyone grunts and cranks out symbols furiously trying to get an upper hand for the next five minutes.

They sometimes sound polite and civilized, these language skills of ours, but we’re just a breath away from our ancestral tree-hopping marsupials and primates. Too bad we can’t admit it. We’re making so much noise it’s getting nearly impossible to listen. Facts are “Fake News” and vice-a-versa.

If we could but admit to being throughly confused, puffed-up, glorified grunting symbolists we might stand a chance of getting our egos in check before we grunt our way into something really stupid.