The ideal of a stable society has preoccupied humankind for a long time, perhaps forever. In order to promulgate social stability, diverse methods have been attempted by various systems of governance and leadership ranging from autocratic to democratic, communal to sovereign, hard-fisted to liberal. All approaches, however, necessarily have to deal with outliers, those individuals and movements that occupy space outside of mainstream society.

Outliers include those who reject common values, engage in behavior considered criminal or “deviant,” and/or generally act and look “different.” How society deals with outliers invariably includes exclusion, rejection or punishment. In the past, religious outliers were classified as heretics and like Giordano Bruno, burned at the stake by the Catholic Church for expressing their beliefs. Artists exploring new subjects, materials or creating social commentary have been shunned, dismissed or called crazy, like Vincent Van Gogh, whose works were not admired until after his death, or Andy Warhol, dismissed as a charlatan at various points in his career. Criminals are arrested, confined and punished; those deemed mentally unstable are medicated or institutionalized. In short, the outlier “problem” is both historical and ongoing.

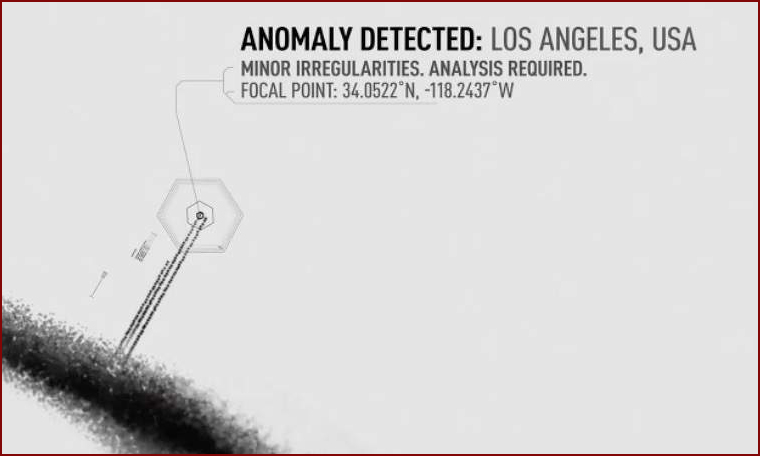

Despite the way society treats outliers, both malignant and benign, they fascinate us and are the subject of an endless stream of books, movies and television programs. Some outliers initially considered malignant are later lionized as brilliantly heroic. Presently, far more attention goes to malignant outliers rather than benign. From serial killers, drug kingpins, and perpetrators of violence of all kinds to super heroes, vampires, zombies, ghosts and evil spirits, outliers currently occupy the lion’s share of commercial entertainment. The recent season of Westworld, for example, largely focused on the way in which Artificial Intelligence decides to deal with outliers in the future; they are identified (see image above) and then confined in suspended animation.

This raises the question: if some outliers are dangerous, why are we so fascinated by them? Freud tried to explain the connection between deviance and normalcy, seeking his answer in the unconscious, infancy and primal urges like sexuality. His premise that underlying conscious life there dwells a deep, largely unknowable realm opened up a Pandora’s box of rational inquiry as to the nature of mind. That the workings of the unconscious mind influence our everyday behavior was as controversial when proposed as were Darwin’s ideas about evolution of the human species, but both theories have gained widespread acceptance as truth.

Each of us embody these truths, but their opacity increases our curiosity and fixation on them. Accordingly, creative fantasy life often consists of speculation and hypothesis about human nature, albeit disguised as theatre; it’s not entirely different from the rituals of ancient cultures who enacted stories while wearing frightening masks or the gruesome rites of the Aztecs, who publicly tore the hearts out of living victims to ceremoniously satisfy the blood lust of their imagined gods.

The impulse of malignant outliers, the violence of their unconscious, produces actual violence, and human cultural history is filled with it. Author Georges Bataille was fascinated by the violence we perpetrate, and its role in history. Over the course of his lifetime, he ultimately concluded that the homogeneous unity of society is always subject to rendering at the hands of heterogeneous outliers, and government itself can fall into the hands of malignant outliers. In his 1933 essay “The Psychological Structure of Fascism,” Bataille described the particular mechanism through which malignant outlier government is established and flourishes.

Essentially, Bataille observes, the heterogeneous malignant outlier psychologically represents formerly rejected elements of society or the distressed working class. By appealing to the exuberant, angry energy of the “distressed,” a malignant leader emerges in the role of populist “sovereign,” assuming cult-like status and promising to “clean” the nation of its unhealthy and unclean aspects. This call for unity (the etymology of “Fascism” is “binding together”) masks violent and often sadistic imperatives of power. Duterte in The Philippines, Erdogan in Turkey, Putin in Russia and Trump in the United States are all expressions of the rise of the malignant outlier.

Under Trump we’ve witnessed the separation of children from families, the caging of asylum seekers, construction of a steel border wall, denial of healthcare to the poor, the characterization of immigrants as “rapists” and “murderers,” and a retreat from international cooperation on a host of critical issues. A naked appeal to “America First” nationalism, calling white-supremacists “very good people,” encouraging “Brownshirt-like” gun-toting protesters to demonstrate against COVID-19 policies, all smack of Fascist behavior. Combined with constant lies and demands for personal loyalty from government officials, these features neatly fit into Bataille’s observations from 1933 during the rise of Adolph Hitler.

Many Americans are suffering from states of dissociation, an inability to accurately see or understand what is happening. Deflection, distortion, denial and dismissal all play a role, alongside lack of education and critical thinking skills; the stress of a lethal pandemic and the prospect of economic collapse add their own macabre energy to the situation. Whatever fascination the character of the malignant outlier holds for America, at the moment its danger lies uncomfortably close to the surface.

The amazing thing about Trump is that someone as ill informed, thoughtless and impulsive can be so effective politically. We all talk about how awful he is, but not much about his evident genius – what does it consist of? He doesn’t know much, he doesn’t think, he is undisciplined.