Our conceptions of joy, love, companionship, creativity, aesthetics and the like are the stuff of human culture, highly meaningful to people but of no particular consequence to nature. If we ruthlessly consider the fundamental role of animal life on earth, we quickly arrive at one inexorable conclusion: animal life is just so much fertilizer.

Wild animals that perish in the forest become food for lesser creatures, quickly decompose and return to the soil, where they then nourish plants and microbes upon which life depends. This cycle of birth and death has sustained life on earth for billions of years. As best we can tell, only the human imagination is concerned with matters of life and death, other animals existing in the moment without regard to contemplating the meaning of life. Whatever fear is felt by wild animals, it is not fear of what happens after death. When it comes to that particular notion, only humans suffer.

To ease our suffering, we’ve developed a variety of ways of thinking about and dealing with death. Paleontology has revealed that well before the advent of Homo Sapiens, homonids regarded death as something notable. Neanderthal burial sites have been uncovered that include the remains of gathered plants and flowers carefully arranged around a corpse; clearly, death had special meaning even for these ancient beings. Homo Sapiens brought an expanded view to death and burial, eventually designing elaborate structures and rituals dedicated to conceptions of death and an afterlife. Human sacrifice on an industrial scale by the Aztecs and the construction of massive Egyptian pyramids are but two of many such examples.

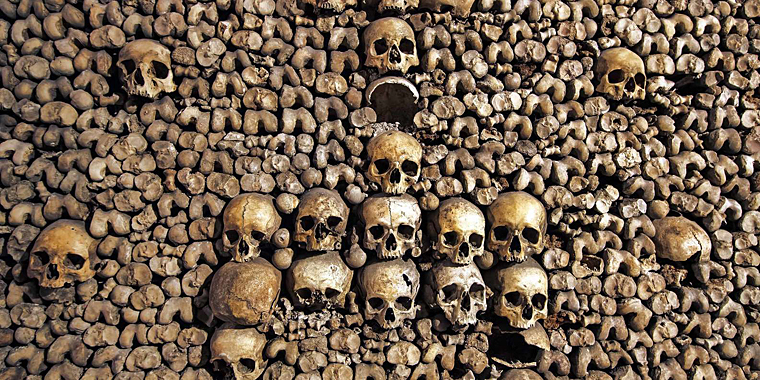

More recently, dealing with deceased people involved keeping and caring for bones, and vast repositories called catacombs were created to house them. White bones cleaned of all tissue, preserved as the pure essence of an individual, became sacred relics of a past life. Today, however, our methods of disposing of dead bodies are subject to scientific rationalism; reduced to ashes in furnaces or embalmed with preservatives and then encased in boxes buried within concrete vaults, our dead are swiftly hidden away from view.

Despite our discomfort with them, the deceased have reemerged as leading characters in a plethora of books, films and television shows; rotting zombies, blood-hungry vampires, decaying mummies and the like haunt our leisure entertainment alongside other-worldly ghosts and goblins of our imagination. Despite hiding our dead, our imaginations will not let them rest.

Burial techniques are changing a bit, with “green” methods beginning to appear and be accepted as legal. Using human ashes as compost, memorial forests are being planted and promoted as an ecologically sound alternative; the substantial greenhouse gasses produced during cremation, however, belies such claims. It remains illegal to wrap a dead body in burlap and bury it in the backyard where it will slowly decompose.

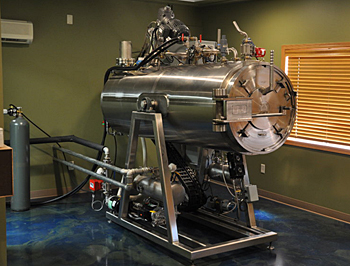

The newest, and perhaps most ecological approach, uses very hot water combined with an alkaline additive to rapidly dissolve all but bones and teeth, which are then crushed, boxed and conveyed to the surviving family. The resulting liquid is sterile, looks like fish emulsion (the liquified remains of fish), and also happens to be a superb fertilizer. This returns us full circle to the fundamental role of animal life in the environment. Sprayed on growing crops, human emulsion produces vigorous growth and enhances plant health. Setting sentimentality aside, with seven billion people on the planet, it’s a sound idea.