Homo sapiens are pattern-finders and base their behavior on anticipating patterns or pattern variance. Making prognostications on the future, using reason and thought to replace simple instinct, largely distinguishes humanity from other animals. A change of seasons, for example, triggers instinctual hibernation behavior in bears. People, on the other hand, make rational plans in anticipation of seasonal change: stockpiling food, chopping, and stacking firewood, or relocating to warmer locations. When we observe patterns changing, we adapt.

I find it fascinating to read books written in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s about the future. The authors forecast and imagined what was going to happen, but I don’t have to imagine; I know.

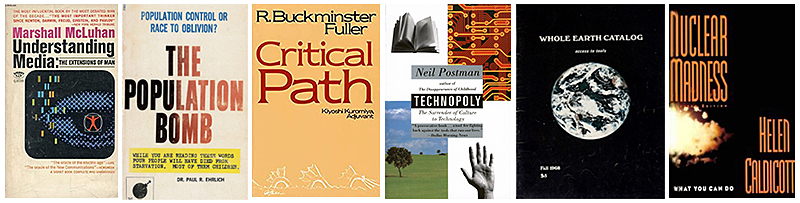

Authors Marshall McLuhan, Paul Ehrlich, Buckminster Fuller, Neil Postman, Stewart Brand, Helen Caldecott, and others observed patterns of human behavior that raised concerns about the future. Over-population, global warming, the effects of communication technology, the danger of nuclear weapons, and the weaknesses of finance capitalism were, among others, topics of prediction, and in most cases, the prognostications have been borne out. We can’t say we weren’t warned, we were, but on the whole warnings were ignored for too long or entirely. This raises the question: why do we so easily ignore studied predictions about the future?

The answer may partly rest in how easily each of us forms opinions. Humanity does not share one mind; rather, individuals are free to make up their own minds. Although decisions are made by groups, and entire cultures center around specific belief and moral systems, individuals are free to form opinions, even if social, religious, or legal prohibitions are in place to prohibit their expression. Freedom of thought is one price we pay for overcoming instinct.

Today, “influencers” are all the rage online, individuals who through combinations of charisma, charm, verbal skills, appearance, creativity, presentation skills, and ideas capture the attention of other individuals. In this way shared opinions may become widespread belief, even when such opinions defy scientific truth or validity. The art of prognostication, once the rarified realm of experts and scholarly specialists, is now practiced by any old Dick and Jane.

Since prognosticators of the past have been so readily ignored, perhaps the current democratization of prognostication doesn’t matter much. Opinions and ideas are disseminated so quickly today via Twitter, TicTok, Facebook, etc. that the flood of prognostications are largely irrelevant; by the time they’re offered, the world has changed.

We used to think of time as fixed and constant; a minute was a minute and a second seemed very short. In our electronic age, although a minute is still a minute, our experience of time has been radically altered. Just as the introduction of perspective and foreshortening into two-dimensional art shifted human perception of distance, so too a foreshortening of time has shifted our perception of events. Things seem to be happening more quickly, as if the speed of time itself has changed, often leaving us behind.

It was McLuhan who predicted this would happen. Way back in the 1970s, he anticipated that as the speed of information increases, rates of loss and obsolescence simultaneously increase; hence, the traditional foundations of culture would be challenged too rapidly. He predicted that with the widespread availability of electronic communications technology, humanity would re-tribalize; that the process of bringing people closer together would simultaneously drive us further apart. He prognosticated correctly, but alas; we didn’t listen.

Spot on!