While growing up I was instructed to refer to adults as Mr., Mrs. and Miss; to do otherwise was a sure path to being chastised. This rule of etiquette applied universally as a sign of proper respect. The basic premise was that using an adult’s first name without permission was a no-no, and this rule applied even to the way adults referred to each other. In this way, questions like, “May I refer to you as Charles?” entered the lexicon. In grammar and high school, all the teachers were Miss, Mr. and Mrs., no exceptions.

When I was in my late teens, a shift occurred; the title Ms. entered the language. Women, frustrated by the sexist implications of being identified in patriarchal society as either married or not, resurrected the 17th century Ms. as an alternative to Miss or Mrs. In this way, a neutral title for women was introduced, and is now commonplace. At the same time, the etiquette of using a title remained; in polite society one continued that formal practice.

Things remain much the same today, but we are on the cusp of change. It’s unclear what the specific nature of that change will be. Driving the shift is the social pressure of gender identity, the reluctance on the part of a growing population to the binary designation male or female. The LBGTQ community prompts a reexamination of the vestiges not only of patriarchy, but of caste and status.

Titles emerged in western society as honorifics of royalty and the conduct of the royal court. Kings, queens, and members of the royal family were always addressed by title, Majesty, Highness, and in more intimate surroundings, Sir and Madam. Sir and Madam were also bestowed on members of the nobility, along with titles such as Lord, Lady, Duke, and Duchess. Knights were Sir this and that. Over time, aristocrats became Sir and Madam as well, while servants were addressed solely by their last names. In this way, caste designations kept the hierarchal order intact.

In America, where caste was more explicitly reserved for racial purposes, the titles of Mr., Miss, and Mrs. were applied to white, adult society, all derived from Master. The use of a single name was reserved for servants, workers, enslaved persons, and non-whites. As social equity increased, titles were subsequently applied to all adults, and so it was that children like me were taught. In American political life and the military, honorifics still abound; senators, mayors and military officers continue to be formally addressed with titles.

Marxist egalitarianism in early communist countries like Russia sought to eliminate class and gender distinctions, thus honorifics were replaced with one only: “Comrade.” This leveled the utopian playing field, even as the underlying reality of hierarchal power dynamics remained firmly in place; “Comrade” is now tainted by the history of communism. Similarly, “Citizen” defines legal status, and is exclusive.

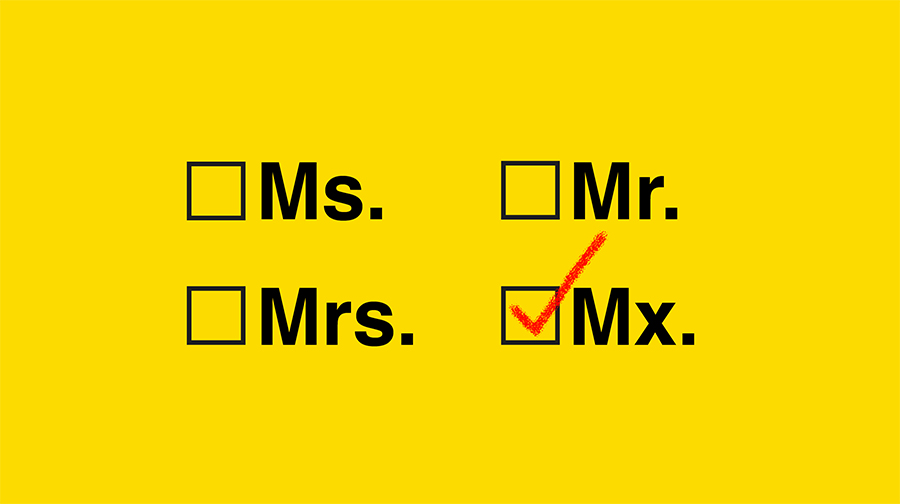

The issue of identity has prompted change in the use of personal pronouns – he, she, him, and her, supplanted by “they” and “their” for those who decline gender specific pronouns. It’s only a matter of time before the use of honorific titles changes. “Decline to state” now appears on many forms but does not adequately address concerns; when it comes to titles, there is no ready substitute for Mr., Mrs., Ms., and Miss, and although Mx. was added to the dictionary in 2017, I’ve not seen its wide adoption. Perhaps the time for Mx. has come.