Chapter 28

The lights in the Gittleman library flicker, and then go out. Despite their best efforts to maintain the home’s systems, each passing decade has taken its toll. Parts that once were available are no longer made. Old circuits and relays reach the end of their effective lives. “The Gittleman home is a metaphor,” Len considers, “it’s analogous to the lifeline of Pierre.” Pierre too, is flickering, progressively in and out of awareness as his mind and body prepare for death.

Len and Pierre have spoken about death, and Len knows what Pierre’s wishes are. “Wrap me in a bedsheet and bury me in the garden, Len,” he asked one day several years ago. “If you can find an apple tree to plant over my grave, I’d like that, too.” “Sure, father,” Len responded, “whatever you want.” Of course, apple trees are not available, but Len sees no value in bringing that up.

Len heads down to the utility room to see if he can fix the circuitry and get the lights back on. He passes Pierre’s lab room and the placental tanks, now silent, dark and drained of their nutrient fluid. After spending some time, he discovers a burned-out relay, and replaces it. A monitor in the lab lights up, and displays a picture of a tiny green creature, what Pierre called Kermit. Kermit is where it all began, this quest of Pierre’s to cement the legacy of human intelligence by creating a new, hybrid life form for a transformed planet. Len steps to the monitor and gazes at the image, thinking to himself, “You are my ancestor, Kermit. I honor you.” He then reaches forward and pushes the off switch.

Heading back to the library, he finds Pierre awake and sitting up. This has been Pierre’s persistent sleep pattern, episodes of nodding out and then waking up repeatedly during the night. Too frail to wander, Pierre simply sits, and unless spoken to will sit in silence until he once again nods off. Len is grateful that Pierre is content to remain seated and worries when Pierre moves about by himself. Now well over 100 years old, Pierre is vulnerable to falling; no doctor is available in case of a fall or accident. For this reason, Len rarely leaves Pierre’s side; his devotion to Pierre’s well-being is boundless.

“I replaced a dead relay,” Len says to Pierre. “The lights should work reliably for a while.” Pierre nods, and and brings his two white and bony hands together before his heart in the mudra of gratitude. “Are you hungry or thirsty, father?” Len inquires. Pierre shakes his head. “How about a cup of Oolong Tea, hmm?” He gets no response and can tell that Pierre is fading again. Len pulls his chair next to Pierre and reaches out to take Pierre’s hand in his own. He’s struck by Pierre’s thin and sinewy hand, bereft of all muscle. They remain this way while Pierre slips back into slumber, and then Len moves to the bookshelves. Daylight begins to fill the library through its one uncovered window. Another night has passed.

Although he is intimately familiar with the contents of the library, Len has not examined every nook and cranny. A wooden panel under the bottom shelf catches his eye, and touching it, he realizes it opens. Using his fingertips at the edge, he swings open the panel to reveal a stack of dark gray archival boxes. His skin signals his excitement by flashing yellow and reaching in he takes out the box on top. “The archives of Leonard Gittleman” says a small white label affixed to the top. Curious, he places the box on his lap and pulls of the cover; a stack of papers meets his eye, typewritten and yellowing. Len had seen typewritten sheets of paper before, but never this many. Carefully, he removes the document on the top. At its corner, a rusted paper clip welds several sheets of paper together.

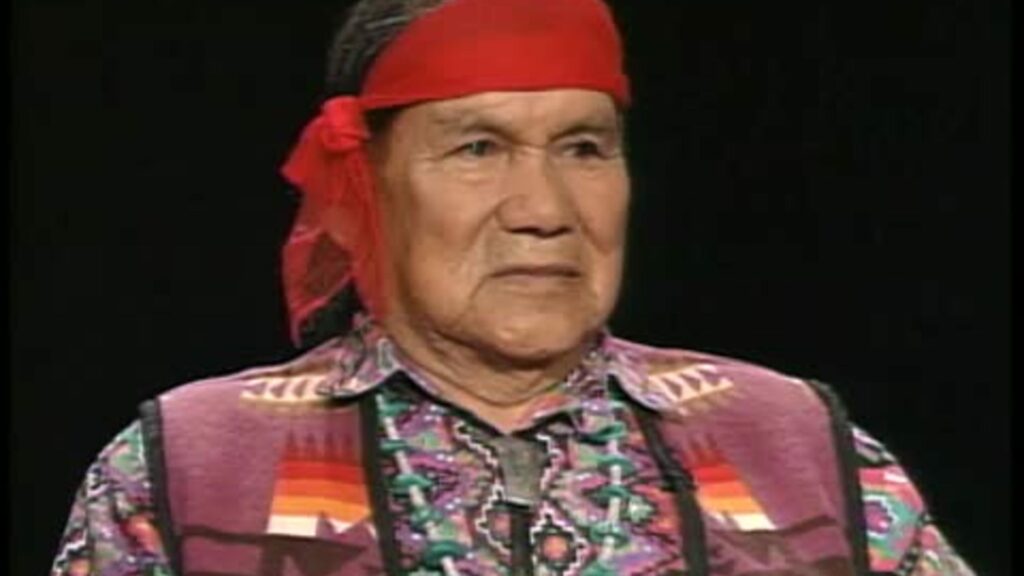

As he reads the document, he realizes it is a transcript of a conversation between Leonard Gittleman and a Hopi Indian elder named Thomas Banyacya transcribed in the late 1970s when Leonard was a graduate student at UCLA. He knows nothing of the the Hopi, an ancient tribe located in the western United States, and makes a note to himself to find out more about them. His gaze falls on one segment of the paper, titled “The Hopi Prophesies,” and he begins to read it.

“And eventually it’s going to break down, see just like they are disturbing all nature now around us, they are really digging into mother earth for everything and they’re creating something out of it and polluting the air and water and everything and disturbing things up above now. And all these things, eventually, it’s going to destroy us. So that is why if this knowledge of these things are put out and explained in a way that people will realize that if we don’t stop this thing, it’s going to destroy us. Like total destruction.

There be flash floods and there be erosion started and many other things happening. Before when it rained there was a slow drizzle all night maybe two or three days, just soak the ground real good. Springtime we have flowers you can hardly see the ground all over this field at one time; it was just beautiful flowers of all kinds, birds and wild animals out there, real good fertile valleys out here and there’s no washes out there. All around, when the water runs off in springtime, you sees waters all over, it covers this whole valley, and that’s the way it was during that period that’s the way the Great Spirit told him to take care of it. Once its been disturbed and people neglect it then things will start happening. That’s going to lead toward destruction so that if we don’t check this now, well, it’s going to happen. Anyway, that is why we have a chance to stop it; if we learn or understand this we have a chance to stop it. And in order that Great Spirit know that I, we can’t, if we can’t stop it even though we know and understand, we don’t know how to stop this, that’s why He has appointed three purifiers to have to do that with arrow power and might, with understanding that they have at that time, as to how they are going to purify this land.”

Len sets the paper down, feeling a combination of shock and sadness. “So, they knew,” he thinks to himself, “not just scientists but indigenous people have known for a very, very long time. These ancient people knew what was going to happen, prophesied it. Now the ‘purification’ has happened, just as their Great Spirit foretold. Were Homo sapiens so stubborn and fearful that even the most straightforward information was ignored? Pierre was right, sapiens destroyed themselves with their eyes wide open.”

He reaches for another box, fascinated to discover this treasure trove of material. This one has family photos and documents: Pierre as a baby and toddler, Leonard as a young man with his parents, the death certificate for Pierre’s mother, June, who died when Pierre was only three. Len discovers that Leonard, like Pierre, was raised in Montreal and moved to Halifax in his twenties to follow a Buddhist teacher from Tibet. Leonard then went on to become a university professor, specializing in cultural studies. Len finds Leonard’s diploma from graduate school. He’s struck by how much like Pierre Leonard looked. He reflects on the fact that he has no biological parents, and wonders if that experience would feel any different than his feelings for Pierre.

Placing everything back in the boxes except for some photos of Pierre as a child, he stacks the boxes neatly in the cupboard and closes the door, planning to examine Leonard’s archives on another occasion and looking forward to showing Pierre the childhood photos he’s found. “This is as close as I will ever get to a family,” he says to himself, and closing his eyes, leans back into the bright patch of sunlight streaming from the window.