Be it ritual figures made for spiritual practices, decorations placed on everyday objects, hieroglyphs applied to rock faces, images created using colored sand, applied body paint, feathers or jewelry, so-called “folk art” is the natural and often spontaneous expression of the unity of creativity and culture. Thus “primitive” cultures enjoy the oneness of art and life. North and South American indigenous populations, African tribal societies, Aboriginal Australians, South Pacific Islanders and the like; for such people art was, and in some cases still is, a way of directly connecting with powerful symbolic space independent of words, a reality that transcends rational mind.

Any genuine form of art is an exploration of this primordial space, and this is true in modern western society as well. Western culture, however, has separated art from life by making a series of distinctions about what constitutes “legitimate” art. Our legitimate art, unlike indigenous folk art, is all about money.

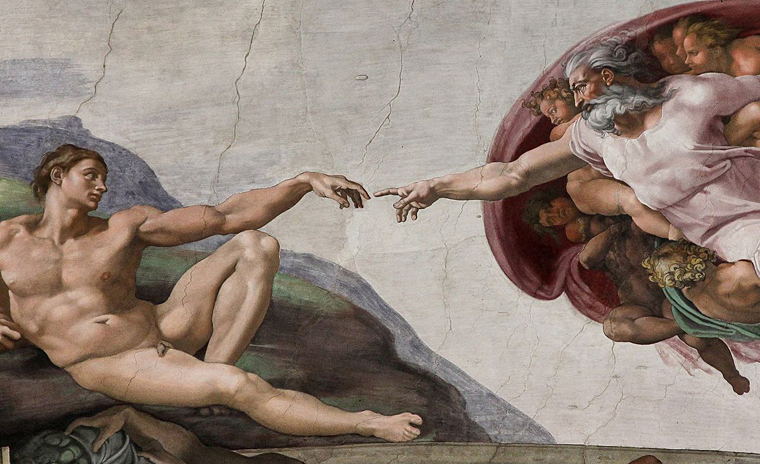

It was during the Renaissance, with the advent of the likes of Michaelangelo and DaVinci, that the social status of artists began to change from anonymous worker/servant to individually recognized artisans of reputation. Their works were commissioned by the Church, of course, and thus were subject to limitations of religious doctrine; nonetheless, their artistic genius could not be suppressed.

The later tremendous commercial value of great Renaissance art was dependent upon evolving global economics and the industrial revolution. Art historian Kurt von Meier notes the connection between the creation of Art Museums and the slave trade between Africa and the American colonies of England in his monumental work “A Ball of Twine.” The first 65 paintings placed in the Tate Gallery in London, for example, were donated by Sir Henry Tate (1819-99), made wealthy alongside his partner Abram Lyle in the highly profitable sugar, rum and slave trade. Such trade spawned an industrial ship-building enterprise in which the three-foot high space allocated for each slave was equal to the height of rum barrels which replaced them on the return trip to England. You can still find Lyle’s Golden Syrup in fine grocery stores.

In considering art’s commercial value (or for that matter, folk art), we cannot ignore time. Setting aside subject, materials, culture, meaning, intended use, color, form, or condition, antiquity alone means money. The older an object, the more valuable it becomes. The antiquities market is booming, and museums are filled with objects stolen over the centuries by western colonial powers. Only now are some of the former colonies regaining possession of such purloined “booty.”

An industry of appraisers, auction houses, dealers, galleries, museums, critics, publications, attorneys, insurance companies, restorers, forgers, thieves and police has grown up around the world of art. Art as financial investment codifies and completes the final separation of art from life; works of genius are kept locked away in dark, climate-controlled vaults where the curious will never set eyes on them.

“De gustibus non dispudandum est.” This Latin phrase translates as “There is no dispute in matters of taste.” Thus love of art is highly personal. When it comes to what is valuable art, there is great dispute, indeed. “The Scream,” a decidedly disturbing image by the artist Edvard Munch, was recently bought anonymously at auction by a private individual for nearly $120 million. Now that’s a lot of love.