Our fixation with moving screen images is perhaps the most obvious example of our fascination with change, but whether fast or slow, change unfailingly captures our attention. Change is so constant and pervasive that it is at times overwhelming, but change itself is really the only constant in our lives. We’re it not for our profoundly powerful powers of denial and delusion, inhibition and suppression, the reality’s constantly changing bombardment of our psyches would render us insane.

The universe and time itself are unfolding around and through each of us, each moment the irrevocable transition of a constantly changing present we call “now.” We can join with the moment of “now,” but cannot halt it; nor can we slow it down; our only option is to make choices. “Now” is a moving target; the choices we make are always either in response to a change we have experienced or in anticipation of change we expect.

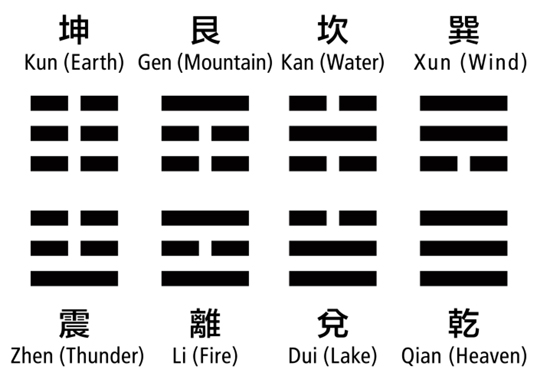

The ancient Chinese book of wisdom, the I Ching, is also called The Book of Changes, and offers 64 hexagrams representing basic types of situations and choices we commonly face. By throwing coins or yarrow stalks and recording patterns, we place ourselves in sync with the moments of time, and the result produces an oracle of contemplation.

Some people consult the I Ching in pursuit of an answer, looking for advice on how to solve a problem or dilemma; a description of a state of mind or condition is described, and a possible way of working with it suggested. The images and metaphors of the I Ching are often obscure, and the relationship between the two trigrams that combine to create each hexagram often point to the duality of mind. Commonly, however, the oracle points to a shift to one or another hexagram for consultation through what are called “moving lines.” In this way, change itself is introduced into the process, forcing us to drop attachments and to understand our role in the universe as observer, not simply participant.

Painted scrolls from China’s classical period always feature magnificent natural scenes of mountains, clouds, forests, and rivers; the people in such paintings are always pictured as very small and almost insignificant. Such treatment indicates a philosophical view about the nature of being: that humanity is simply a tiny part of something much larger, much grander. Accordingly, the descriptive images in the I Ching are often of mountains, rivers, clouds and natural forces such as thunder. It is the antithesis of our western view of the ascendancy and importance of the individual, as amply illustrated in artist Andy Warhol’s garish, larger-than-life portraits of Hollywood celebrities like Elizabeth Taylor.

By linking human experience and choice to metaphors of nature, the I Ching reminds us of our connection to the greater natural world and seeks to unify the experience of being rather than highlight separateness. It wisely points to the patterns of nature, what emerges and changes, to suggest how we might get out of our own way. Our emotional penchant to try to stop time and make “now” last forever distracts us from the truth of change.

Thus, the I Ching is not a magic 8-ball; it does not make infallible predictions or tell the future. Rather, it is a device, a methodology intended to divert us away from preoccupations of self-absorption and deliver us gently into the arms of uncertainty.