As you my readers know, I customarily limit my essays to about 570 words, but in this case I’ve departed from that convention and have written this much longer piece. I hope you find it interesting.

Events propagate in a branched structure, and inflection points are those nodes in a branch that become a point of growth in a new direction. Some events sustain established directions while others become points of diversion, some for a short while, others for a lifetime. Like trees, growth in human life happens simultaneously at many branches, but some become dominant while others wither. It’s difficult to identify major inflection points in life as they happen.

In looking back at my life one of those major inflection points was meeting Kurt von Meier in 1969. Our intersection propagated a branch that grew in an entirely new direction. I can imagine what my life would have been like had I not met Kurt, but no imaginings could be as interesting as what’s happened.

At twenty years of age, I was living with my girlfriend Peggy in San Francisco in the converted attic of a Victorian house at the northwest corner of 25th and Diamond Street. Having moved from New York City, driven away by frigid weather and overbearing parents, the two of us set up house in a city we’d never known.

Peggy was working for the Harold E. Oram Company, a firm that managed mailing lists for major non-profits, that in an age before computerized databases were widely available. With offices in New York and San Francisco, she was able to transfer her employment to the West Coast, providing us with income from the very beginning of our move. Through her connections, I got a job as a file clerk at The Thomas A. Dooley Foundation, downtown on Post Street, and that eventually led to hearing about an opening at Golden Gate University’s print shop; I applied and was hired as an offset press operator. The two of us became working stiffs, catching Muni and commuting to work like perfectly ordinary adults.

At that time the 35-Eureka bus traveled from a stop near Castro and Divisadero Streets, where we’d transfer to it from a streetcar traveling up and down Market Street. Eureka Street was a steep climb at the base of Twin Peaks, like many of the neighborhoods in Noe Valley, and the 35-Eureka would shift into its lowest gear, inching up the steep incline at a mere five-miles-an-hour. A glance out the window revealed a massive green mansion with turrets and gingerbread, which always fascinated me. Later, I discovered it was called Nobby Clarke’s Folly, named after the ill-fated guy who built it. On the downslope portion of its route, it would make the turn onto Diamond Street, and I’d hop out at a bus stop right in front of where we lived at 25th Street.

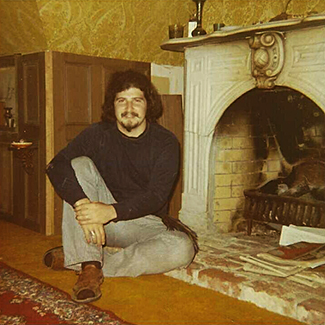

Our attic apartment was really something unique. The couple who lived downstairs, Jane and Chuck, had inherited the home from Jane’s aunt, and before moving downstairs to the ground floor had undertaken an extensive remodel of the attic. They gathered second-hand materials from a slew of Victorians that were being demolished in the city’s Western Addition; that massive project consisted of eliminating an eight-square-block area of run-down old homes considered a slum. The black residents, mostly renters who considered it home, were forced out to live in other parts of the city, like Hunter’s Point. Such was the nature of so-called urban renewal, the displacement of poor populations for their replacement with up-scale housing.

Materials for Jane and Chuck’s remodel were easily available and inexpensive. Accordingly, they obtained a carved, white marble fireplace, wooden wainscoting, floor to ceiling wooden kitchen cabinets, stained glass windows and doors, and gas-fed brass chandeliers. The slanted walls were covered with flocked wallpaper, some of it red and some of it gold. In the end, the one-bedroom apartment looked like a turn of the century whorehouse. A new staircase on the south side of the building led to the second-floor entrance. It was glorious, and only cost us $150 a month.

It was while headed home at the turn onto Diamond Street that I noticed some hippies working on a storefront near 24th Street, and the next time at that spot I got off the bus and walked over to where they were working. I called myself a hippie; since arriving in San Francisco, I’d let my hair grow longer, and started growing a mustache. And of course, I smoked pot, a lot.

Turns out those hippies were busy converting the retail space to a restaurant, building tables and benches, and constructing a small, open kitchen in one corner of the inside space. After stopping by to chat, I learned they were planning to open in a few months. At the time, 24th Street in Noe Valley, and Noe Valley overall, were downtrodden. The retail and commercial boulevard looked more like 1940 than 1970, and featured empty storefronts, and second-hand stores like Lucille’s You Name It. A new restaurant coming to the neighborhood was notable. I watched the progress of the new eatery over from the bus, and just as predicted, it opened in a couple of months: Diamond Sutra Restaurant: Tantric Cuisine read the name on the glass door.

Peggy and I made a visit for dinner right away, and everything about the place was different than any restaurant I’d ever experienced. The kitchen in a back corner was open on two sides, providing a view of the action behind some waist-high counters. The menu was written in chalk on a blackboard; there were no printed menus. The long tables were made from enormous slabs of redwood, their edges still covered in bark with shiny tops in acrylic. Along the walls were long-running benches; overall there were no two-tops or four tops, but a couple of large round tables capable of seating 6-8 people. One wall was covered from floor to ceiling by a huge mural painted by Noble Richardson depicting mountains, sky and a verdant valley.

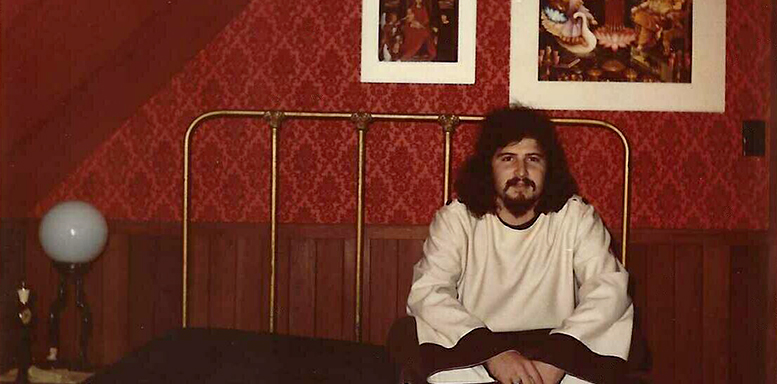

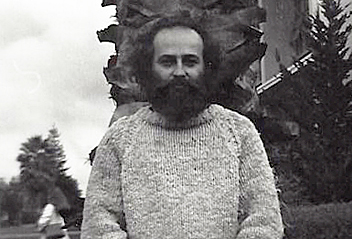

Jene LaRue and his wife Diane, plus Tom Genelli and his girlfriend Judy Plummer were the driving force behind The Diamond Sutra. They all seemed to work in the kitchen as well as cover the table service. And then, of course, there was Kurt von Meier; he just seemed to be there, simultaneously taking it all in while bussing dishes and welcoming diners. Bearded, dressed in exotic, ethnic clothing, and sometimes wearing a black hat with a silver and turquoise hat band, Kurt exuded presence, both magnetic and intimidating. From time to time, he’d erupt in gales of laughter at something he or someone else had said.

The food, and the menu was limited to two or three main choices, and was as striking and different as the decor, a fusion of world cuisines unlike anything I’d ever run into before. Indonesian Gaddo-Gaddo salad, vegetable curry, tamale pie, pumpkin ice cream; new items would appear each day on the menu depending upon the whims of Jene, Tom and occasionally Kurt. On one notable visit, I bit into pea-sized chili pepper so intensely hot I literally lost my breath for a while; Kurt was watching and grinned ear to ear.

The Diamond Sutra became a cool place to hang out, and Peggy and I visited regularly, getting to know Jene, Diane, Tom, Judy, and Kurt better and better over time. Most of them were older; Kurt, Tom and Jene were each in their early to mid-thirties, but we shared our hippie outlook on life, smoked pot, laughed a lot and enjoyed food and cooking. Over time, we became friends, enough so that we’d spend time together before the restaurant opened. Tom and Judy lived in an apartment around the corner, and Jene and Diane a few blocks away on 26th Street. Kurt, on the other hand, had a place in Napa Valley, which at the time he called the Diamond Sutra Ranch, located in Oakville.

In Buddhism, the Diamond Sutra is one of the most renowned teachings. I didn’t know much about Buddhism then, but I’d heard Kurt expounding on all things Buddhist plenty of times by then. Much of what Kurt had to say was way beyond me, and often incomprehensible. His style of interaction consisted of spouting off in one arcane direction or another while peering into my eyes to see what reaction I had and either nodding, laughing, or making a funny face in response. I tried to keep up; he was fascinating and entertaining, but it was impossible to follow or track his frames of reference. Often, I’d just nod or laugh; sometimes I’d respond in words – he’d pause, and either enthusiastically say “yes!” or “that’s horseshit.”

In time I learned that Kurt was an art history professor, a favorite of Princeton’s Irwin Panofsky, widely regarded as the father of modern art history. When I met him, he was teaching at Sacramento State University. He didn’t talk a lot about himself; over the next 40 years I learned all about his past, but very slowly and I didn’t fully discover the full story until after he’d died at 77 in 2011 and I inherited his voluminous archives. Suffice to say, he’d had a remarkable life of world travel, education, experience, and friendships, and being part of it was life-changing for me.

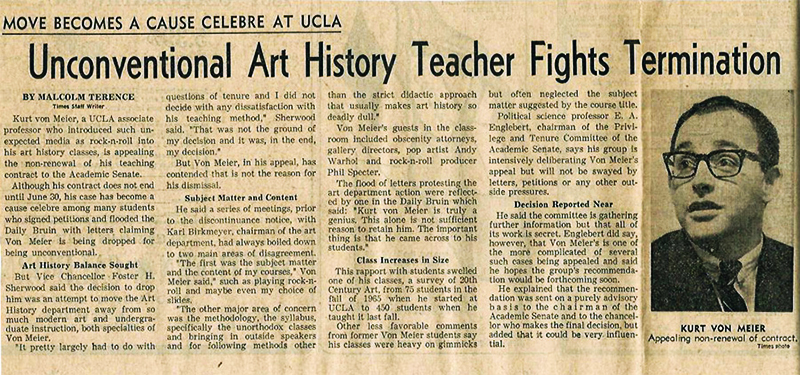

Kurt von Meier was a polymath with a nearly photographic memory. He spoke several languages and was as conversant in advanced mathematics as he was in art history. He loved being theatrical, and his university lectures were as much performance as information; he was also a troublemaker with a native dislike of authority, bureaucracy, and institutionalism. It was these elements of his character that had gotten him into trouble as an assistant professor of art history at UCLA, prior to his teaching at Sacramento State.

As I uncovered in his archives, when his teaching contract was not renewed at UCLA, it became headline news in the L.A. Times. Kurt’s had become the most popular classes at the university, where usually sedate and rather boring art history lectures had, under Kurt’s deft hand, attracted up to 450 students at a time, rather than the usual 75. By combining performance art, lectures devoted to the history of Rock n’ Roll, roiling critiques of art and society, and guest lecturers like Andy Warhol, Lew Reed, Joseph Campbell, and Phil Spector, Kurt managed to gain the widespread love of his students, the ire of UCLA’s administration, and the jealousy of his peers.

His situation at UCLA wasn’t helped by his love of drama and controversy. A devotee of media critic Marshal McLuhan at the time, he took one class to the Santa Monica pier to participate in ceremoniously throwing a black and white television into the Pacific Ocean. He forced his graduate students to attend a 24-hour seminar, schlepping them around L.A. to, among other activities and places, watch planes take off and land at the airport, visit retail department stores to ask strange questions of the salesclerks, travel packed into two vehicles, one a pickup truck where they sat crowded in the truck bed, and keep to a tight schedule. Perhaps his most controversial act was during the UCLA Experimental Art Festival held on campus, where dressed in a white suit, Kurt performed an art piece supposedly created by Jose Que, a Mexican artist of Kurt’s imagination. The piece consisted of building a tower of books, including a white, leather-clad Bible, atop a tinfoil wrapped Weber barbecue, setting them ablaze before a stupefied crowd of students and then opening the act to discussion. To Kurt academic freedom at the University meant everything; not so to the powers that were.

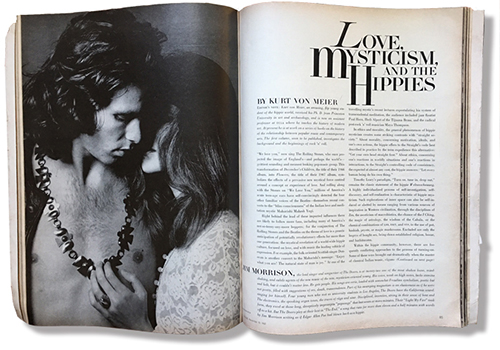

Despite a growing reputation as a brilliant, Princeton University trained art historian who was regularly featured in publications like Art Forum, Art International, Arts Canada, and even the pages of Vogue, Kurt was let go, and spent two years plus looking for another teaching position before finally landing at Sac State.

One weekend, Peggy and I visited the Diamond Sutra Ranch for a day, which was, in the vernacular of the times, mind-blowing. For lack of any other description, it was a commune, a gathering of a dozen hippies living a rural lifestyle at a small ranchero nestled between grape vineyards and bordered by the Napa River. A grove of enormous timber bamboo filled an area behind an old farmhouse, and the front entrance was shaded by a massive 700-year-old oak tree. Various vehicles were parked in the driveway circling the oak, including Kurt’s white Volkswagen Beetle, which had been repainted in colorful psychedelic fashion by Noble Richardson. Beyond the bamboo grove sat an enclosed swimming pool, circa 1930. Some barns and corrals were a few hundred feet from the farmhouse, where a horse named Misty Moonlight was housed and chickens roamed. But without question, Kurt ruled the roost, and was the grand master of ceremonies.

With his long, full beard and dark complexion, Kurt looked rather like a middle eastern version of Cuba’s Fidel Castro, and knew it. For this reason, and the striking appearance of his psychedelic VW, Kurt was a regular target of the California Highway Patrol as he drove from Napa Valley to Sacramento on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday. When pulled over, he took it all in stride, presented his doctoral university credentials and joked around, cautiously, with the patrolmen. But his appearance offered other opportunities.

While visiting Peggy and I at our attic apartment, Kurt suggested we all go out to a fine restaurant for dinner, his treat. We settled upon a fancy French restaurant, l’Orangerie, and I grabbed a phone to make a reservation for three. While doing so, Kurt told me to ask if they had a dress code, and indeed they did. “Jackets and ties for the gentlemen, evening dresses for the ladies,” I was told. Kurt went on, “Ask them if they will accept holy men in native garb.” I did so, and after a pause was told holy men in native garb was acceptable. So it was our reservation was made. We three then proceeded to attire ourselves in robes, wraps, scarves, and beads and headed off to dinner.

Upon arriving at l’Orangerie, we approached the front desk where the maître d’ was in attendance and presented ourselves. “Reservation for Dr. von Meier,” Kurt pronounced in his most stentorian voice. The maître d’ looked us up and down, paused and then smiled. “Ah yes, the holy men in native garb,” he said. “Right this way.” We were taken to an otherwise empty private dining room, Kurt ordered our meal in French, and we were treated like royalty. That was Kurt.

As the year progressed, Peggy got pregnant, and we thought about whether our apartment would work for three of us. By the end of her term, our relationship with the Diamond Sutra gang was tight, and Tom Genelli mentioned that he’d seen an ad for an home in the hills above St. Helena in Napa Valley, about twenty minutes north of Oakville and Kurt’s ranch. By then I’d quit my job as a print shop employee at Golden Gate University and had opened a graphic design studio with my former roommate at Rhode Island School of Design. Peggy had quit her job in anticipation of giving birth. Living in the Napa Valley near friends sounded great, and we made an appointment to see the house for rent.

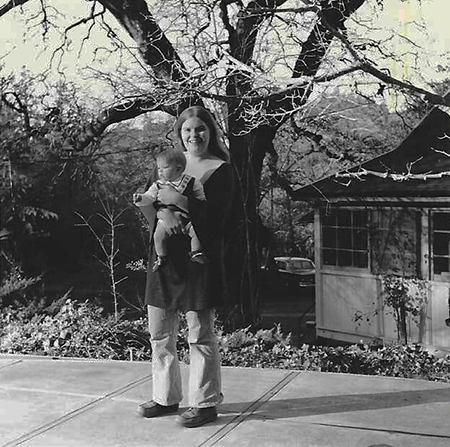

I’d acquired an older, early 60s Mercedes Benz four door sedan. It was dark green, weighed as much as a tank, and looked grand. We pulled up in front of an entry building at a resort just outside the town of St. Helena named Meadowood, and went inside to meet with it’s owner, Freeman Nichols. Turns out the house for rent was one he’d built for himself and his family while Meadowood was being built. It was located at the end of Mund Lane, a dirt stretch off paved Mund Road, that winds its way through oaks and scrub brush in the foothills to the east of the valley. “Go to the end of the Road. There are two houses you’ll see; the one for rent is the one that’s not green,” Nichols said. At $180 a-month, it was something we could afford. We drove out, looked, came back to his office, and signed a lease. We moved in about a month after our daughter, Zoe, was born in September.

“Valley View Farm” read the letters in a wooden carved sign at the driveway entrance, although the view from the house was not of Napa Valley, but a smaller meadow and hillside. Our new home was located on the eastern side of an 800 ft. high Napa Valley foothill, and at the bottom of the other side was Meadowood, a small resort and housing development with a nine-hole golf course. Today, Meadowood is a Relais-Chateau property with acclaimed restaurant, spa and luxury lodging, but back in 1971 it was modest. The house that Freeman Nichols had built was modest as well, a single-story home with two bedrooms. Outside, he had built an in-ground swimming pool surrounded by a patio; his kids names and a footprint from “Rinty” were impressed into the concrete.

The hillside behind the house was studded with dozens fruit trees in various states of health, the legacy of its past an orchard. As the fruit season progressed, we counted over fifteen varieties of plums alone, from small purple Italian style to varieties I’d never seen and have never seen since. Some were green and tasted like honeydew melon; others were golden and tasted like apricots. All were popular with the population of local deer, who we’d hear choking and spitting up plum pits during the summer. One apple tree had seven varieties of apples grafted on it. Some apricot, peach and fig trees rounded out the collection.

A hike over to the other side of the hill revealed the genesis of the name Valley View Farm. A wooden viewing platform, lichen covered and with some sections falling apart, provided a stunning panorama of the entire Napa Valley, stretching from Mt. St. Helena to the North all the way to San Francisco Bay to the South. Some aging wooden chairs provided seats. It was spectacular.

But the real curiosity at Valley View Farm was the old, green farmhouse and its three residents, Gordon, Beverly, and Fred. All three were elderly gentlemen, even Beverly, whose last name was Hills, or so I was told. Gordon seemed to be the guy in charge, and he promptly introduced himself and the others shortly after we moved in. Bev liked to swim in the pool, and we agreed to share the upkeep in exchange for his right to continue to use it. Fred, I found out, was 100 years old, born in 1870 in Ireland. He’d walk haltingly to and from the green house to a shed in the driveway using a cane in each hand. Once in the shed, he would spend hours using a small axe and mallet in his sinewed hands to split eight-inch-long chunks of wood into smaller pieces, later to be burned in a wood burning stove in their kitchen. Gordon, whose full name was Gordon Jackson, would regularly buy a supply of wood specifically cut to eight-inch lengths to satisfy Fred’s activity.

I’d visit Fred from time to time as he split wood, and we’d talk. I’d never known anyone as old as he; his mind was still sharp, but his voice had risen into a very high register, sounding more like an elderly matron’s than a man’s. His eyeglasses were so thick that while looking straight at him, the blue of his eyes filled the entire lens. I had to yell when we spoke; his hearing was terrible. Periodically, he’d ask me to move the large, cut log he sat on while working and I’d heft it to the new location he desired. “Ah, Hercules!” he’d swoon.

On one occasion I asked Fred how he felt about men walking on the moon, which had happened recently. “Oh, Larry,” he cooed, “you know how it is. Men must have their toys!” We’d chat about this and that, but Fred repeatedly turned every conversation to the same subject, how he’d not gotten along with his Irish father and because of that his father had bequeathed the family farm to Fred’s younger brother. For Fred, this had been the ultimate betrayal, a branch of energy that propelled him out of Ireland in humiliation and travel to the United States at the age of seventeen. “I worked here and there and eventually became a follower in the ministry of D.L. Moody.” I must have heard this story two dozen times over the course of the two and one-half years we lived at Valley View Farm and sensed that Fred had spent the better part of his last thirty years reliving deep disappointment and shame.

Beverly seemed to be the least complicated of the three; he listened to KGO talk radio constantly, carrying a transistor radio with him while he was outside at the pool. He’d also embark on long walks in the hillside, using a thick walking stick. Only over time did I discover his eyesight had largely failed him and that he navigated at the periphery of his vision. “Did you hear about the dangers of chicken skin?” he asked me one day, having heard about it on the radio.

Gordon Jackson was altogether different, a mysterious though affable presence who would ferry Fred and Bev to SmorgaBob’s restaurant each weekend in his green Chevrolet Impala. He always seemed to be on the go, driving to and from Valley View several times each day. Not too long after Peggy and I had settled in, Gordon stopped by for a chat to ask how we were doing and tell me a bit about himself and his friends.

When I inquired about a what he’d done for a living, he hesitated a bit. “Well, for quite some time I made a living as an astrologer. Do you know about astrology, Larry?” Like my 60s cohorts, I knew my sign as well as Peggy’s, and asking “what’s your sign?” had become a signature part of hippie conversation. Beyond that, I was a novice. “How does one make a living as an astrologer?” I asked. He smiled, “You can chart the astrology of corporations as easily as charting the astrology of individuals. I’d cast corporate charts, make investments based upon them and advise others on investing, as well. I also wrote articles for leading astrology publications and magazines.” Now that was interesting; he seemed to be perfectly sincere in what he was saying, as crazy as it seemed to me, a twenty-two-year-old, middle-class kid from New York.

He dropped by again a day or two later, carrying some magazines with him. “I thought you might like to see these. I used to write articles under a couple of pen names, like Milo Mills and Angelo Saxon,” he said affably, handing them to me. I said thanks, and he walked off waving to Peggy who was standing behind me at the door cradling Zoe. Indeed, his articles were there, in publications like Modern Astrology. I was impressed. Gordon started to come by every few days, and I learned a little more about him each time.

I mentioned that he seemed to be quite busy, coming and going several times each day. He told me, among other things, that he was an advisor and caretaker to Jack Davies, owner of Schramsberg Vineyards, maker of the Champagne Richard Nixon famously took with him on his visit to China. He also indicated he advised several other elderly residents in the area, but without telling me in what way he advised them. Gordon asked me if I knew anything about the “laws of seven.” I told him I did not.

The next time he came over he brought a book or two along with him. One was about the laws of seven, and the other The Secret Doctrine, a big, fat volume by Madame Blavatsky, one of the founders of the Theosophical Society, an institution started in 1875 to study and teach the wisdom of the ages stretching back to the philosophers and mystical traditions of Ancient Greece, the Pythagorean’s, and others. It was premised on the idea that divine wisdom is accessible to those who properly seek it, and that the holders of such wisdom – Grand Masters – transcend time and space. “I think you’ll find this interesting,” offered Gordon, handing me the Blavatsky book. “Look it over and next time we meet we’ll talk about it.”

Over time, I began to get the feeling my relationship with Gordon was headed in a new direction, intensifying, and changing. Our discussions were getting longer and happening more regularly, almost every other day. I didn’t want to be rude or unfriendly, and Gordon was quite interesting, but I began to wonder if he was more than a bit unhinged, and if all his talk was madness.

During one visit, Gordon, Gordon noticed our upright piano, and asked if either of us played. “Peggy plays a bit,” I replied. “Ah, that’s lovely,” he said softly. “I used to play concert piano.” This seemed to me a moment to find out if Gordon was full of shit or for real, and I went for it. “Really?” I responded, “would you play something for us?” “It’s been a long time,” he replied. “Please?” I asked. He nodded and sat down on the piano bench. He placed his hands lightly upon the keys, silently, closed his eyes and began to play. It was beautiful. He played a classical piece entirely from memory. “Schubert,” he said when he was done. I was stunned, gob smacked, and began to believe – despite my doubts and cynicism – that Gordon Jackson was the real deal.

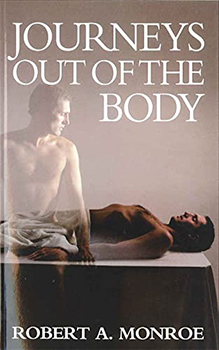

He gave me Journeys Out of The Body, by Robert A. Monroe, a book about the Astral Plane, and Monroe’s personal experience of leaving his physical body and traveling to a different, higher reality. The next time we met, and by then we had been meeting for months, Gordon dropped the bomb. “All this is real, Larry, and I know it because I communicate with the other world. Would you like to know more about that?”

I was torn. A part of me now realized that Gordon had singled me out – as an apprentice, a disciple, a student – and that prospect both intrigued and frightened me. I was a new father and in a major relationship, and yet what Gordon was offering was alluring. Setting my second thoughts aside, I said “Sure.” “Alright,” he said, “to be continued.”

I’d heard talk about Aleister Crowley, supposedly a powerful adept, magician, mystic, and occultist with a decidedly mixed reputation and unearthly stare. Tarot cards, of course, had seen a resurgence of popularity among hippies, and as I’ve mentioned, asking “what’s your sign” was a virtual rite of introduction. Overall, however, I’d never taken any of this terribly seriously and was often suspicious of those who did. And yet, and yet, Gordon kept surprising me with his range of knowledge, talents, and claims. Take Fred, for example.

“Did you ever wonder, Larry, how it is that Fred is so active at over 100 years old?” Gordon asked me later. “Yeah,” I replied, “he’s quite remarkable.” “Well, Fred’s a solid specimen, for sure,” he said nodding, “but there’s more to it than that.” “Like what?” I asked. “Well,” Gordon went on, “a number of years ago, Fred developed severe arthritis in his neck. He was in constant pain, couldn’t sleep and was suffering terribly. I contacted entities in the other world, and they performed psychosurgery on him. Totally cured him, as you can see.” He leaned in towards me, and whispered, “I’m in contact with Hermes Trismegistus.” Once again, I was confronted with an idea that sounded just, plain, crazy.

I didn’t know Hermes Trismegistus from Seymour Rosenberg, but decided to look him up. I went to the local library and there he was, an Ancient Greek demigod comprised of elements of Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth, and purported author of Hermetica, a compendium of esoteric knowledge. The encyclopedia did not mention that he was a friend of Gordon Jackson.

The books and conversations kept coming, including a massive tome entitled The Secret Teachings of All Ages by Manly P. Hall, Founder of the Philosophical Research Society. This richly illustrated, over-sized volume was divided into entries on all of the world’s major esoteric, mystical traditions, an encyclopedia of the occult. I poured over it for a week and ended up with more questions than answers. I told that to Gordon, who simply smiled and nodded his head sagely.

By now six months had passed, but strangely, Peggy had not only tolerated my relationship with Gordon, but seemed intrigued herself. It was as if Gordon had cast a spell upon us both. But things were about to change, and suddenly.

About this time, Kurt and the ranch family stopped by for a visit. Between caring for a baby, traveling to San Francisco a few times a week to go to the design studio, and my involvement with Gordon, I’d not had much contact with him. He brought some gifts with him, as was his style, and something to smoke, and we sat outside talking and laughing. I told him about Gordon, and all that had happened. He looked uncomfortable, and his usual happy-go-lucky manner turned serious. “Be careful, Bean,” he said, using my nickname. I was surprised, thinking he’d find all this occult business cool. “Of what?” I replied. “Just be fucking careful,” he said sternly, “this can be dangerous stuff.” He seemed positively upset, gathered his crew and departed. I didn’t know if he was jealous or worried or both.

It all came to a head on a perfectly ordinary night. Ordinary nights at Valley View Farm were either deathly quiet or punctuated by odd sounds. One night I was awakened by what sounded like cries of “Help” repeated over and over. I later learned that peacocks had roosted in the large oak in the driveway and what sounded like “help” was their cry. Deer choking on plum pits often punctuated the silence. The scratching of rats inside the walls of the house was always disturbing. But on this particular night, something happened that had never occurred before.

I was lying in bed with Peggy, falling asleep, when suddenly I heard Gordon’s voice as if he were leaning in towards my ear. Of course, Peggy and I were alone, but his voice was clear and conversational. “I’d like you to consider what we talked about today, Larry,” he said. It was then I realized that his voice was in my head. “What!” I thought frantically. “What are you doing in my head!” “Relax Larry, we can talk this way,” he replied, “don’t be frightened.” I was frightened, though, very. I suddenly realized things with Gordon had crossed a line for me and this was far more than I had bargained for.

“Gordon,” I thought, “get out of my head! Don’t you ever do this to me again! In fact, I can’t be your apprentice, I won’t. I’m twenty-two, have a small baby, a business and a girlfriend and I just can’t do this. It must stop. I’m sorry, that’s the way it is.” Then there was silence.

I was shaken and told Peggy about it in the morning. She said that I’d probably been dreaming, but I felt certain about what had happened. Gordon did not come by the next day, or for that matter, for a week. Finally, he knocked on the door one afternoon, smiling and friendly and said, “Hi Larry, I’ve just come by to collect my books.” He didn’t say more, or mention anything else, and neither did I. I retrieved his books and he left. Other than a friendly wave and hello, we never really spoke to each other again.

We left Valley View Farm a year later and returned to San Francisco. By then the Diamond Sutra had become a great success, and far too much work for Jene, Tom, Kurt and the crew. A positive review in the San Francisco Examiner by Patricia Unterman did them in. She’d interviewed Kurt, who introduced himself as Jose Que, the busboy, and he’d shared the recipe for Gaddo-Gaddo. Shortly after, the Diamond Sutra was sold. Later on, Jene, Tom and Kurt wrote about it all – Cuisine Imaginaire, they called it.

I ended up splitting up with Peggy, quitting the design business and moving to the Diamond Sutra Ranch, by then called the Diamond Sufi Ranch, in late 1973, where I lived for a couple of wild and wacky years. Kurt’s friends dropped by, folks like Alan Watts, destruction artist Raphael Ortiz, isolation tank and dolphin communications researcher John Lilly, various Tibetan Lamas, healers, pot farmers, musicians, artists, philosophers and wackos. The branch of my life that began to grow with Kurt bore remarkable and unanticipated fruit over the next 40 years, but then, that’s another story.

Larry,

That was delightful

Thanks Larry

Your story offers detail to shaping forces and descriptions of personal geography many of us will find familiar. Fun to read

good job, bean. now let’s see the part about kurt.

You certainly haven’t led a sheltered life. I enjoyed hearing about your contacts and adventures.