Chapter Two

“Homo botanicus sounds good,” thought the 35-year-old Pierre Gittleman, his mind wandering away from Thomas Dougherty’s story about the benefits of fasting. Pierre’s mind has been moving a mile-a-minute lately, fueled by his certainty – you could almost call it an epiphany – that humankind’s dominion over the earth is drawing to a close.

“I have more energy, and my mind seems sharper,” Dougherty droned on. “Hey, Pierre, are you hearing what I’m saying? I mean, you ought to try it, see how it works for you; what do you have to lose? Pierre? Hello Pierre! Earth calling Gittleman, come in!”

“Why are you shouting at me?” Pierre fires back, “Fasting. Yeah, I get it, thanks. Listen, gotta go. See you later.” He swivels away, strides down the hallway, and walks smack into the back of someone half his size. “Shit, sorry!” Pierre blurts, escapes into the crowd now streaming out of the lecture hall, strides through the front door and into the warm street beyond.

Back in his lab room across town, where the only noise is the air hissing out of the recirculating vent, Pierre relaxes back into his thoughts, his mind turning to his recent Chemputer Software upgrade and its sophisticated new tools for gene editing and synthetic biology. He’s still amazed with the awesome power at his fingertips, that a keyboard and nested sets of algorithms can direct the creation of new life forms, that numbers and letters become flesh and bone. Admittedly, he’s been pushing the envelope, some might say too far, in his pursuit of knowledge and ground-breaking results, but if humankind’s future is as bleak as it appears, why not, he figures, take things as far and as fast as he can?

Bleak is an understatement. The earth’s atmosphere had changed far more rapidly than anyone had predicted. Even though prognostications made as early as the 1960s pointed to looming climate and population disasters, the world’s addiction to fossil fuels, its sheer momentum, was far too great to reduce quickly; corrupt politics, hunger for money, and leadership by power-craving narcissists sealed humanity’s fate as population and global temperatures began to rise and then shot up suddenly in the mid-twenty-first century.

The world’s nearly eight billion people proved too many to feed: their pure, animal hunger exceeding humanity’s food production capacity. With soaring temperatures, the world’s previously productive temperate agricultural zones began to fail. Spring arrived earlier while summer and fall heat lasted longer. Sometimes winter never arrived. Rainfall patterns changed radically, the polar ice sheets melted, and warming ocean currents responded to their decreased salinity by slowing down or stopping entirely. What had been the breadbaskets of the world relentlessly morphed into scorching, windblown, dusty basins. Potable water became as precious as gold. Starving populations on the move ran headlong into refugee blockades as one country after another sought to protect itself from starving hordes and sequester what food remained. Millions, and eventually billions, would perish as extreme weather, hunger, and epidemic disease relentlessly rolled in successive waves across the changing surface of the earth.

Pierre lived in Halifax, Nova Scotia, once chilly, but now become virtually balmy. Within the protections of its walled city, virtually a city-state within what had been Canada, Halifax was a protected area of self-sufficiency; desalinization plants, tidal and wind-powered turbines, climate-controlled greenhouses, and domed structures supported a stable population of researchers, scientists, agriculturalists, aqua-culturalists, and planners. Most were engaged in studies and experiments dealing with climate modification, but a few, such as Pierre, were striking out in new directions, less focused on solving the climate crisis than developing ways to adjust and cope with it.

His epiphany, when it came, hit him like a thunderbolt. Whatever humanity that would remain on earth would be contingent upon its ability to adapt, and its essential adaptation was coping with hunger. From its very beginnings, perhaps one-billion years after the plant kingdom firmly established itself on earth, animal life was wholly dependent upon eating for its survival. Unlike plants, which evolved to provide self-sustenance and growth through photosynthesis, animal life requires a steady supply of externally available protein, carbohydrates and minerals to survive. From this humble truth emerged the greater array of complex, adaptive systems and senses attuned to sourcing and consuming food; over millions of years this culminated in self-consciousness, culture and human society. From there it was a relatively short leap to introducing technology, industry, and the collective enterprise that would eventually tip the global environmental balance towards instability. The die had been cast at the very beginning; if humanity were to survive, realized Pierre, humanity would have to become something else.

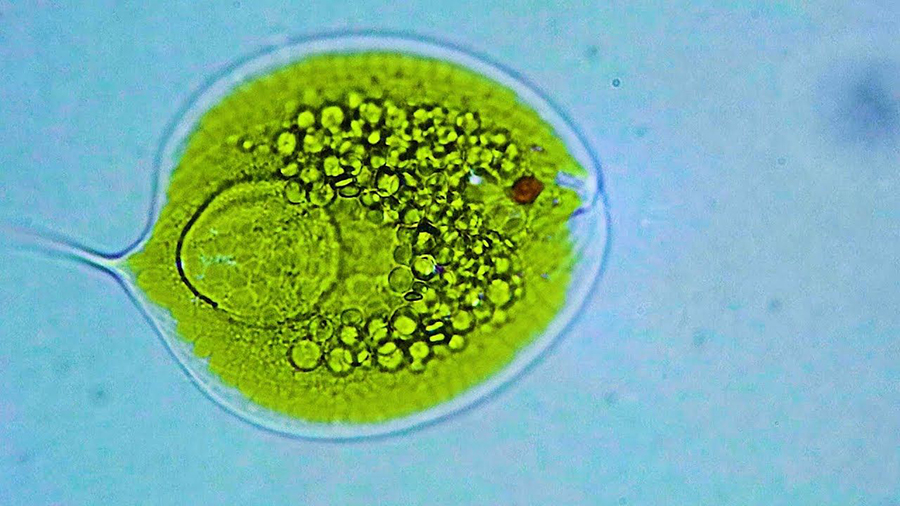

The lab’s silence is suddenly broken by the sound of a timer going off, its steady beeping drawing Pierre’s attention to a small tank of dark green water. Approaching it and turning off the alarm, he selects a clean pipette, inserts it into the water through a permeable membrane, draws out some liquid and lets it drain into sterile, previously covered dish. From this dish, he selects a drop and places it into imaging equipment that magnifies any object by hundreds, or even thousands of times, displaying the result on a color display. He finds nothing.

Undaunted, he removes the first sample, selects another and places it into the imager. Still nothing. This goes on for thirteen hours. He never loses patience or control, each step of his process repeated carefully and patiently. Pierre is very patient; friends would say he is patient to a fault, but his patience is not an accident of nature, but something he has mindfully cultivated for decades at the suggestion of his father, Leonard Gittleman, a Vajrayana Buddhist practitioner who shared his wisdom with his only son. “Patience,” Leonard told the young Pierre, “is a transcendent activity, one of the essential practices of the Bodhisattva. You will accomplish absolutely nothing of value without patience, my son.”

Finally, at the end of his thirteenth hour, an image appears on his display, a tiny green blob, darker than the greenish water in which it floats. Pierre progressively increases the magnification until the blob fills the entire screen. To anyone else, the blob would appear as just that, but Pierre knows better. Pierre knows that he has created a new life form, a living animal that does not need to eat but produces carbohydrates from light itself through photosynthesis. “It looks kind of like a young tadpole,” Pierre says out loud to himself, his excitement controlled by using a measured breathing technique, what his father called Pranayama. “I think I’ll call it ‘Kermit’,” he decides, pulling the name from his memory of a Muppet book his father used to read to him when Pierre was a toddler. “Welcome to our world, Kermit,” he says, and clasping his palms together before him, he slightly bows and softly chants; Om Mani Padme Hum.”

The opening of your novel, Larry?

I’m enjoying, Larry! Keep writing

Green!

Jimmy