In Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001, a pre-human hominid throws a thigh bone high into the air, and in a cinematic transition, the thigh bone becomes a space vehicle in orbit around planet earth. This scene typifies one quality of living things, the way we extend our reach to display ourselves in the space around us.

Displaying ourselves; in higher life forms like people if we’re not noticed we cannot convey a message, claim space or territory, attract the attention of potential mates, or gain personal influence. This human proclivity builds upon instinctual drives we can observe in animals like bower birds, which build elaborate, artful nesting structures, or male peacocks that dancingly display stunning tail feathers.

In ways large and small, people reflect the primal urge to extend their reach beyond themselves into the wider environment. When we speak of “curb appeal,” for example, we’re talking about the extension of “personality” to the outside of a home; it’s a display we make to the rest of the world. Such matters dictate how we dress, style our hair, and even what car we drive. Everything we do embodies statements about ourselves, messages we display to the world not entirely dissimilar to the way a rose displays its petals.

Measuring success today largely relies on getting noticed, either narrowly or widely. Billions are spent each year by people in business in their efforts to get noticed. To do so, every possible niche and opportunity for exposure is explored, and if determined to be viable, marked with displays and messages. These efforts extend into the micro and macro; images, messages, and logos are delivered digitally on social media, physically on billboards and even on the exteriors of jet ramps at airports. So insistent is our need to be noticed that few objects or opportunities get overlooked in the commercialization of public space.

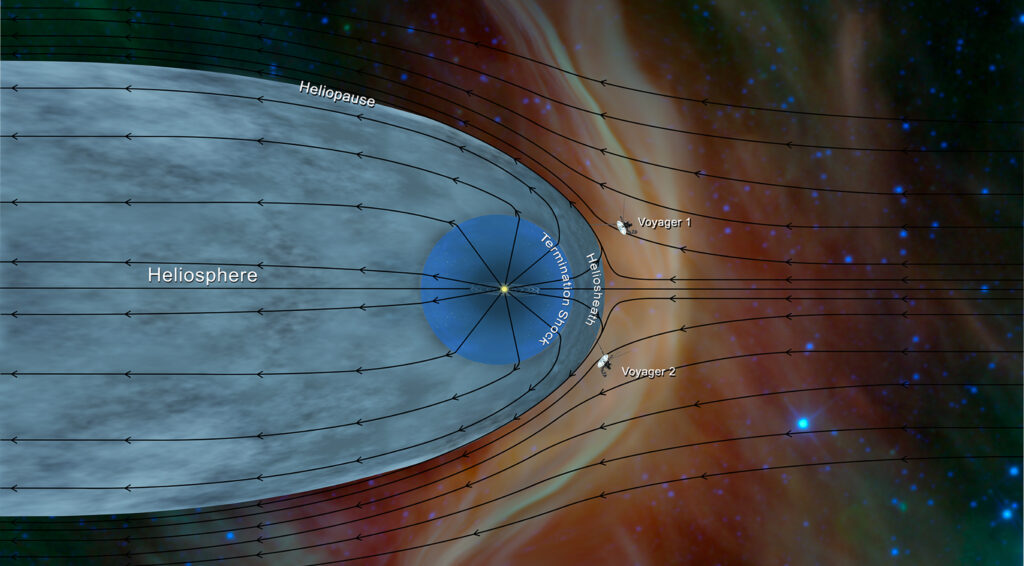

Kubrick was onto something primal about being human, and the pinnacle of our success at getting noticed may be the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecrafts, launched in 1977, “bones” we’ve thrown into the far reaches of outer space. Beyond the heliosphere, 14.5 billion miles from earth, racing through interstellar space at 34,000 miles-per-hour, the two Voyagers carry an informational record of humanity with them, golden phonograph records that contain images, sounds and data about humanity and our home planet, including recorded whale song, the sounds of waves breaking on the shore, crying babies, and Chuck Berry singing “Johnny B. Goode.” If undeflected by another object, in 300,000 years Voyager 2 will approach the star Sirius, located at a distance of 4.3 light years.

At present, we’ve no confirmed evidence of intelligent life anywhere else in the universe, but among its uncountable trillions of stars and planets, advanced intelligent civilizations most likely exist. Should one of them intercept a Voyager spacecraft, we will have displayed ourselves and gotten noticed. By then, it’s also likely that human life as we now know it will no longer exist, but at least we will have piped up among the stars and said, “Hello there, we once were!”

Although their power supplies are nearly gone, communication with the Voyagers is still ongoing, and they are providing us with information about the nature of interstellar space. Voyager 1 and 2 may mark the pinnacle of human existence; it certainly qualifies as our most far-reaching physical display and our showiest achievement.

Loved this!

Nice! I continue to enjoy your essays Larry.

Thanks you for the effort to communicate…

and on such a lofty intellectual level.

Hope your ear is doing well. If not, come

visit in Monterey/Carmel. DrP