Life on earth is very, very old, a couple of billion years, at least, and nearly all the creatures that have ever lived have disappeared. Were it not for photographs, we’d lack a visual record of our recent past, let alone that of our ancestors. As it is, excepting hundreds of years-old paintings, ancient statues, and names on gravestones, relatively few records exist.

From an information theory standpoint, life is a lossy file format. Although genetic morphological data gets transmitted from generation to generation – eye color, hair color, skin color and body shape – the rich inner details of each particular life, the bulk of an individual’s thoughts, feelings, ideas and experiences, get lost. Pretensions to immortality are vainly sought; almost all about us will be forgotten.

Like oak leaves, generally alike but individually unique, our lives drop and dissolve into the cycle of life. Our individual discontinuity is offset by the collective continuity of life overall, wherein the existence of single individuals is essentially moot. As a species, we endure through dynamic kinetic stability: individuals come and go, their significance lost within the long-term trajectory of the species as a whole.

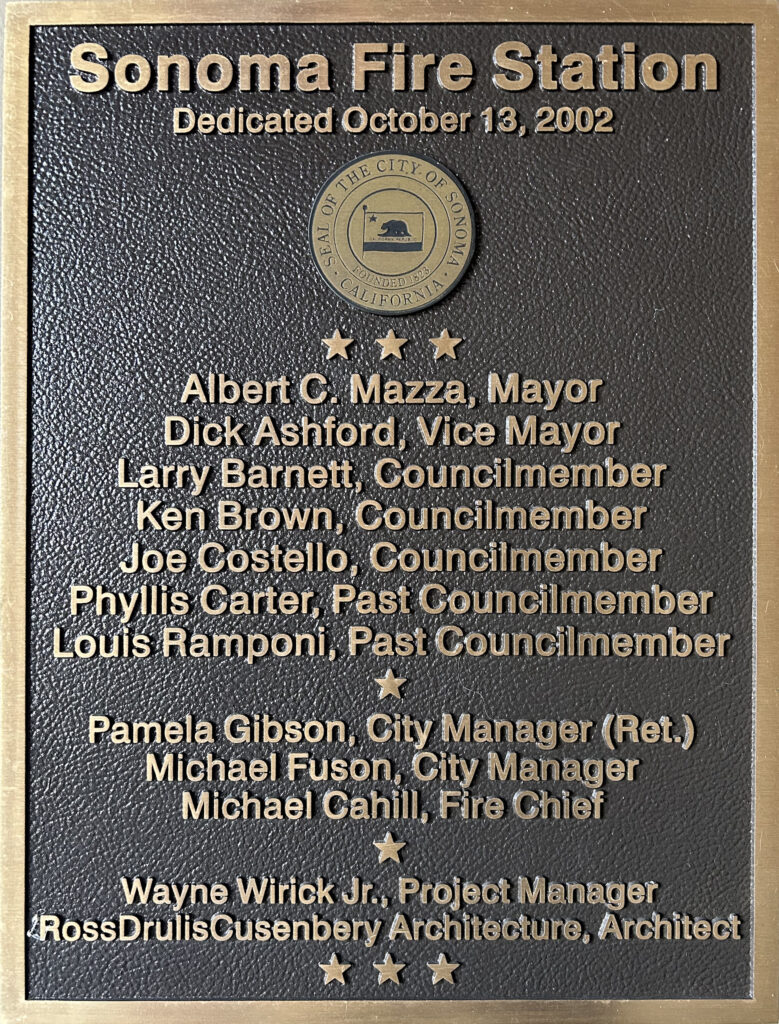

Attempts to cement one’s place in history are generally doomed to failure. Hammurabi and his Code and the Pharaonic pyramids at Giza are notable, but in time those too will disappear. My name on a brass plaque at our local fire station will outlast me, but along with memories of me, it will eventually disappear.

I find a certain comfort in all this, a gentle mercy. Humanity shows many sides, some lovely and beautiful and others horrible and ugly. Time doesn’t respect such distinctions any more than the weather respects national borders. The sun shines on us all, the evil and the good, in equal measure. If that seems unfair, perhaps it’s why we invented heaven, hell, and genealogy.

Looking at a panoramic photo of the 1946 Motion Picture Pioneers convention at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, I found the pea-sized face of my grandfather among many gathered around, linen-covered tables. I’m among the very few alive who can recognize his face; direct memory of my grandfather, his voice and manner, will disappear with me. The other hundreds of now long dead men are just photographic ghosts to me, but since I never knew them, I’ve not forgotten them, either. Earnest men dressed in tuxedos gathered on the floor of a ballroom; they are like fallen leaves on the forest floor.

It doesn’t take long to be largely forgotten, generally a few generations, maybe a bit longer within families. Culturally, the memory of celebrities, politicians, and big movie stars lasts longer, but they too fade away. What can you tell me about Willard Fillmore, the 13th President of the United States? Can you visualize the young face of actress Joan Blondell, and when was the last time you even tried? She was a huge star once, and now just another photographic ghost, all but forgotten. How long will the direct memory of me, you, or any of us last, and how do you feel about that?

The lossy character of life makes no demands, but knowing what we know about death nudges us to contemplate lonely things. Life’s a showy business, yet we will be forgotten. All will be forgotten. In the vastness of time, names, dialects, and perhaps even language itself will disappear. And thus the living world endures.